Gearbox Records master and cut their own vinyl at their studio in King's Cross, London. They also master and cut for outside clients and provide a consultancy service to guide producers, engineers and artists through the potential minefield of vinyl record production. Here they take Ernest through the process of cutting vinyl from source to sleeve.

Cutting vinyl requires the same approach to craftsmanship, dedication and quality as any other hand crafted artisanal activities. Our goal is to make the best records that it’s possible to make at every level, and the mastering and cutting process is crucial to the quality and sonority of the finished record.

The source

Everything starts from the source – the better the quality the better the finished record will sound. Tape with no digital often sounds best, but we can work from any analogue or digital file format. We’ve found that recording a digital source to 1/4” tape on our legendary vintage valve Studer C37 tape machine can radically enhance the sound, almost as if the tape was gluing the music together.

Mastering

The source is then mastered through our all analogue and highly transparent Maselec master series equipment. This is the perfect marriage of vintage and modern to get the best out of the sound.

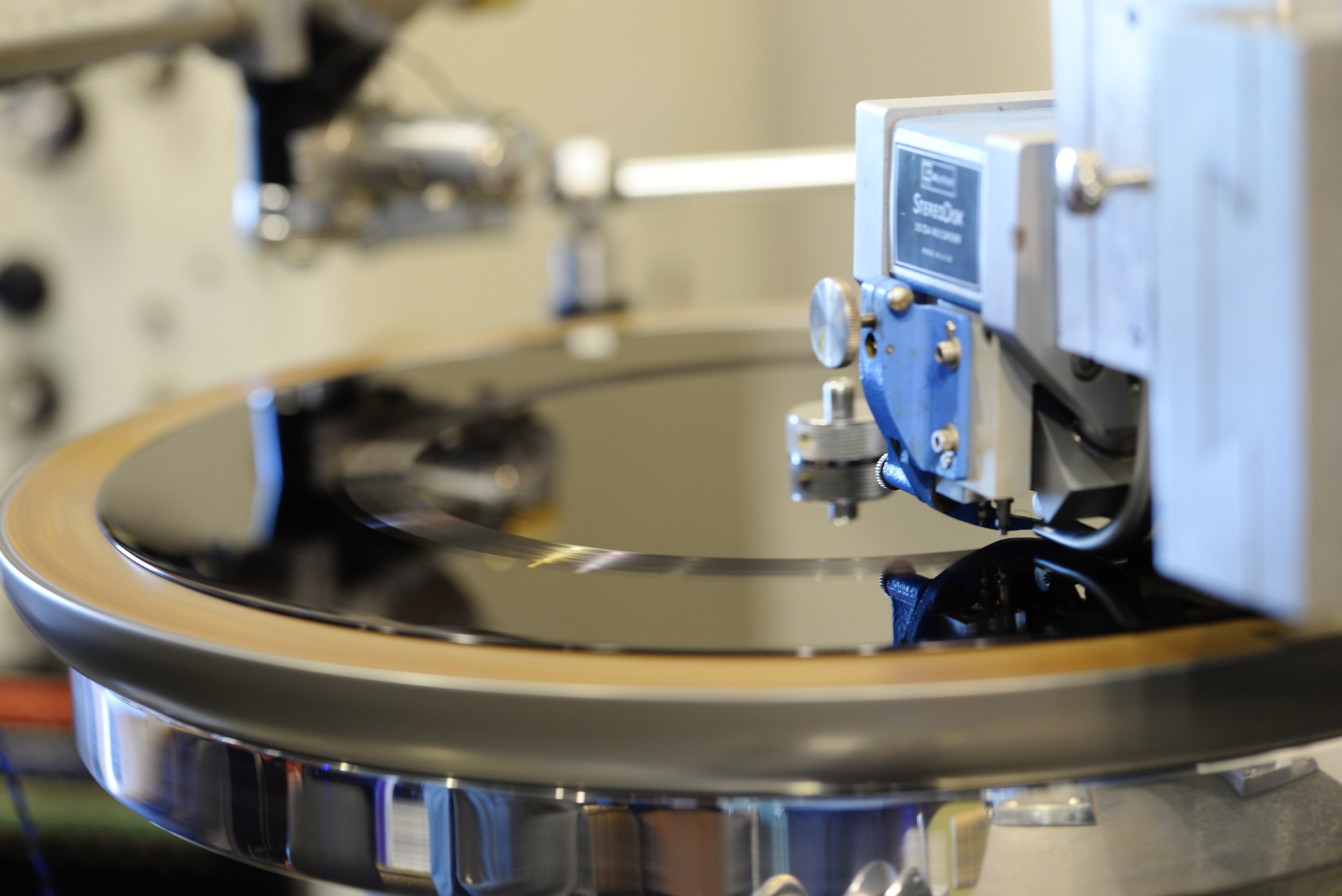

Cutting the groove

This signal is sent to the cutting head of the 1967 Haeco Scully lathe where the groove is cut into a blank lacquer to create the master. Our Scully, with its Westrex amplifiers, is the same set up as Blue Note were using and has no digital preview signal processing for Varigroove. This means we have a 100% analogue chain with none of the jitter associated with early digital converters from the 70s and 80s as in most other lathes currently operating.

Creating the record

The finished lacquers are then sent to Optimal Media in Germany for manufacture. The first stage is the galvanic process which includes polishing and electrolysis to create the metal stampers. From these stampers, hot vinyl pucks are smashed at high pressure, trimmed and cooled to create the vinyl record.

Testing, testing

We insist on the making of a number of test pressings to check everything’s sounding right and there are no technical issues. Meanwhile the artwork is prepared by our designer, and templates sent to Optimal Media, who also do all the printing.

Packing and shipping

Once the test pressings have been signed off, the production run can go ahead and the records are pressed, sleeved, packed and shipped to us for distribution to our dealers around the world. We insist on small vinyl runs of 500 or 1,000 units to maintain the highest possible quality control (a typical stamper can press about 5,000 units), and always use the best materials for covers and appropriate weight of vinyl for each release.

On the turntable

Finally comes the best part – the ritual of preparing and placing the record on the turntable, sitting back and enjoying the analogue glow of music that’s as close to the original source - the singers and musicians who created it - as it’s possible to get. Have a listen yourself.