It was while working in her garden during the first lockdown that designer Rebecca Kaye was struck by the number of birds flocking to her bird-feeder, and the variety of colours in their plumage. Inspired by her love of exploring the natural world through maths and design, Rebecca set out to discover exactly how much colour she was seeing through these avian visitors, and translate the data in a stunning piece of visual art…

Bird Colours Lithograph, by Ploterre

Mathematics, design and the natural world – what led to your harnessing these three things for creating your products?

It feels more like a long, scenic loop rather than a journey to somewhere new. I say that because when I was growing up, the three things I loved more than anything were maths, art and being outside. For various reasons (school timetables preventing you from studying both maths and art, and jobs being very much maths or art based, barely a combination of both), I had to veer off-course before finding my way back.

The loop essentially involved my studying maths, then working with data, then studying design before pretty much giving up my spare time to work in data by day and design by night. This was when I lost my connection with nature.

However, through perseverance over many years, I eventually found a way back to the place I always wanted to be.

What's been the most surprising part of your journey creating Ploterre?

It’s realising how much I love doing what I do. I’ve tried a variety of things in the past that involved an element of both maths and design, but I never felt satisfied. Since coming up with the idea behind Ploterre, blending both design and data – and only using environmental data – I’ve never been happier. It’s the perfect combination of spending time poring over data on a subject that’s really close to my heart, then having the privilege of bringing that information to life through design.

Tell us the story behind your Bird Colours Lithograph – what inspired it, and what was your creative process?

This was pretty much a result of lockdown. As with many people during that time, I found refuge in nature. I’m lucky enough to have a garden, and I set up a work space in front of the bird feeder. Watching the birds fly in and out of the garden made me realise there were so many colours darting across the sky. My mathematical mind wanted to know exactly how much colour I was seeing, and that sparked the idea behind the print.

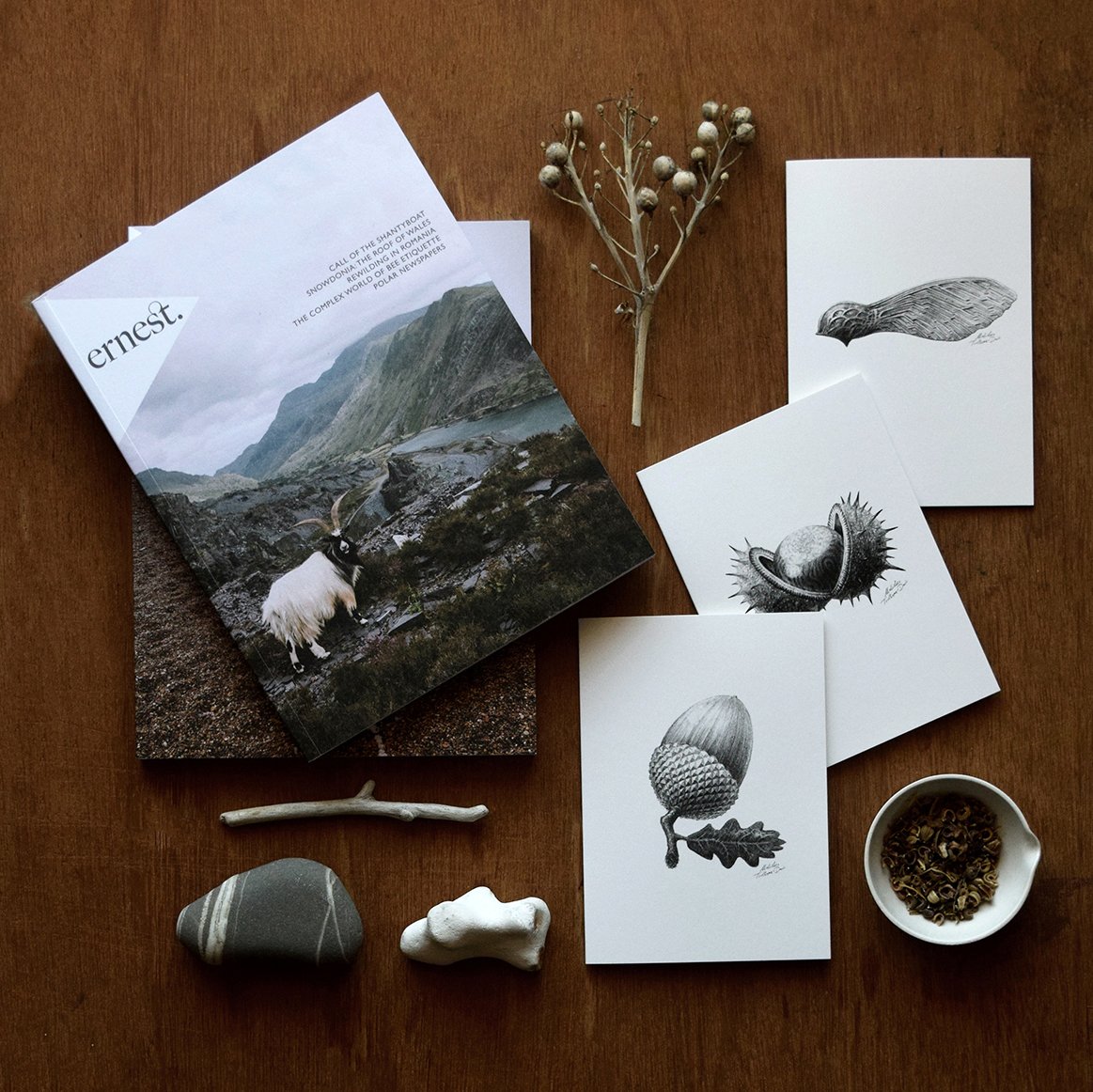

Rebecca’s lithograph charts the colours from the top 20 most commonly sighted birds in British gardens

What is it about mathematics and data you find so compelling?

I’m very solution driven – both in my personal and my work life. I like the fact that maths always has a solution. This is similar with design. There may be a variety of ways of addressing and answering a problem, but you know when you’ve solved it, at least in your own way.

As an example, for the Birds Colours Lithograph, I set out to find out the most frequent visitors to UK gardens, which I found via the British Trust for Ornithology and their Garden BirdWatch survey, and the proportion of their body covered in specific colours (using illustrations from the RSPB). Once I’d decided on a formula to bring these two bits of information together, I’d solved my ‘problem’.

Do you have a favourite piece from your collection?

The Bird Colours Lithograph is one of my favourites because I spent a lot of time working with the data and bringing a variety of information together. It was the process I enjoyed more than anything else. It was also a slightly different output from my other prints – I allowed the process to lead the design and I didn’t set out with a rigid idea of the end product.

Are there any projects you're currently working on you'd like to tell us about?

There are a few new pieces I’m working on that are similar to the Bird Colours Lithograph in both style and process. Most of my work to date has been quite illustrative, showing mountain visuals to describe mountains and illustrating a bothy to communicate bothies. However, my new pieces are more abstract in design and more time-intensive in research. I really enjoy the lengthier research process, and allowing that process to drive the designs. It was the bird print that really opened my eyes to that way of working.

Where do you turn for inspiration, particularly when you're in a creative lull?

Outside! I often find I’m in a creative lull when I’m busy and feel like I don’t have time to go for a ride on my bike or spend time in the sea. But those are exactly the times that I need to be outside.

Without fail, I return from the outdoors refreshed, inspired and so much more productive with my time than if I’d remained at my desk, staring into space.

Tell us about your work space – how does it reflect you?

My studio is a room in my house with two windows, both overlooking trees. I’m based just far enough out of Edinburgh that it’s still easy to visit – for all the amazing galleries – but I also have a view of the Pentlands and close access to the sea.

Since moving to Scotland almost 20 years ago, I instantly fell in love with the country but I don’t think I quite appreciated how much variety of the natural world (from mountains to coastlines and rivers to fields), Edinburgh has on its doorstep.

What's on your bedside table?

Books and lots of them. Predictably, they nearly all revolve around the outdoors. My favourites over the past few months are Homesick by Catrina Davies, Afloat by Danie Couchman, Things I Learned When Falling by Claire Nelson and A Boy in the Water by Tom Gregory.