It's a bit later than anticipated but we're delighted to tell you the Collector's Edition of issue is one is back from the printers, smelling beautifully fresh and inky

We'd like to say a big thank you to everyone who donated to our crowdfunding campaign and helped us send our Collector's Edition to print. The journal is freshly back from the printers and we're sending out copies to those of you who pledged for an issue or pre-ordered through our store page.

It’s been a real joy to revisit our first edition; to think back to the time and thought we put into crafting the Ernest voice, indulging our curiosity and allowing our contributors the space to share their stories.

We’ve had to carefully consider where to update features. Many of the independent brands have gone on to thrive, while others have closed or changed gear – bespoke bicycle makers have become flower growers – and so we often suggest alternatives or ways you can follow the makers in their new endeavours.

We have also added two new stories. ‘A Perfect Clutch’ explores the meticulous research that goes into crafting replica bird eggs, while in ‘Ernest in the wild’, we ask contributors to share memories of journeys undertaken for the journal, from breaking bread at a Greenlandic kaffemik to floating with jellyfish in the Salish Sea.

The sense of community that has grown around Ernest over the past eight years is remarkable, and we continue to feel buoyed by your support and encouragement. Thank you for being part of our journey! We're so excited to share our Collector's Edition with you – let’s take a look at what’s inside…

Inventory

Nautical slang, anatomy of a storm kettle, the Mechanical Turk, how to cook meat underground, the real Moby Dick, a map of shipping regions, summer cocktails and a timeline of forks.

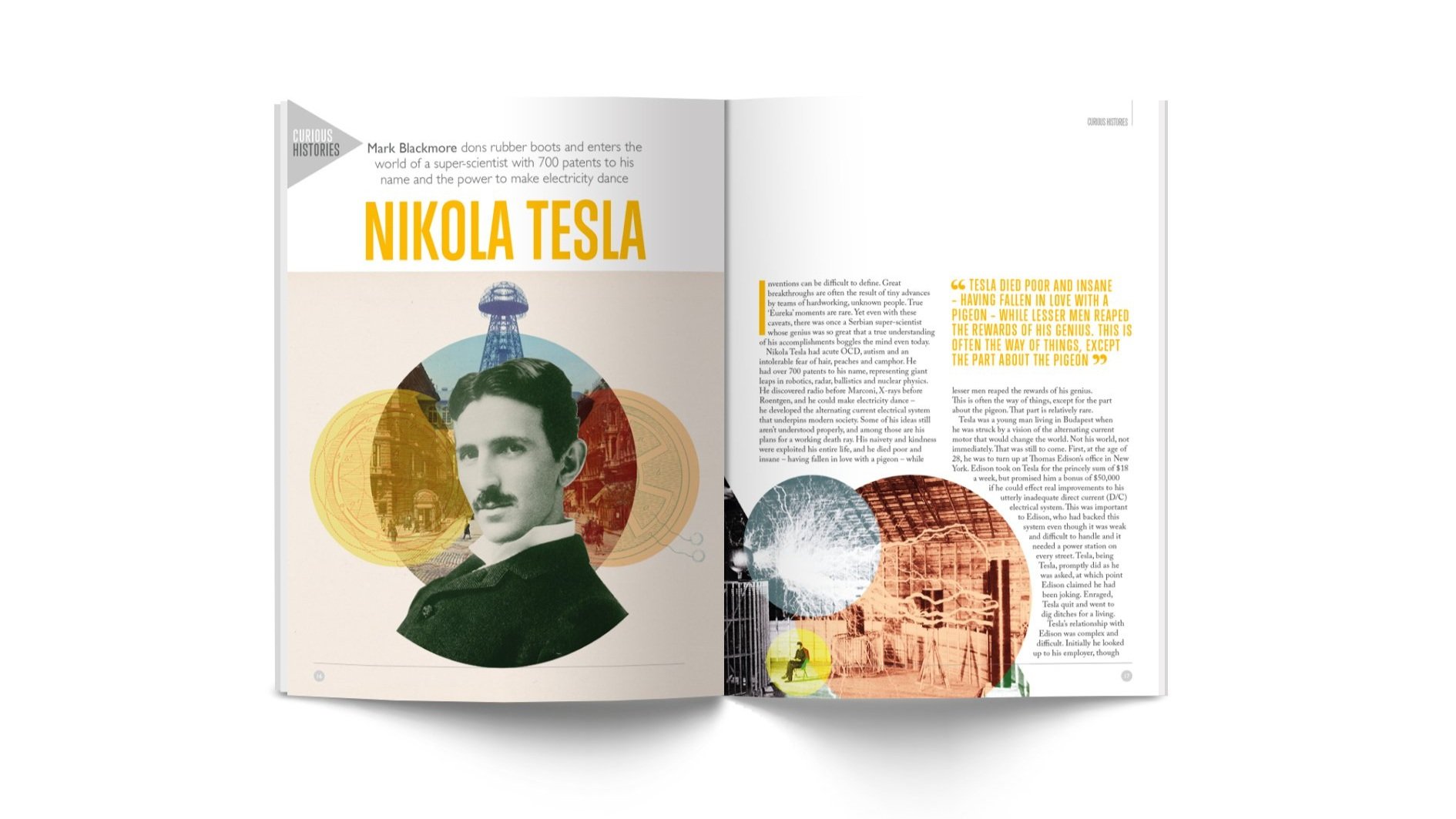

Nikola Tesla

Mark Blackmore dons rubber boots and enters the world of the Serbian super-scientist, with 700 patents to his name and the power to make electricity dance.

Ernest in the wild

To celebrate eight years of publishing Ernest, we asked contributors to share their memories of journeys undertaken for the journal, from breaking bread at a Greenlandic kaffemik to floating among thousands of jellyfish in the Salish Sea.

Last & awl

Meet John Lobb, fourth generation crafter of bespoke shoes, guardian of Frank Sinatra’s wooden feet and boot maker to the future king.

Sea monsters of the northern seas

Duncan Haskell wakens the mythical beasts that slumber beneath our oceans, including an island that drags sailors to a watery grave and a creature that collects human bones in his beard.

A perfect clutch

Editor Jo Tinsley enters the studio of Tony Ladd to explore the research that goes into crafting replica bird eggs.

The Westfjords Watertrail

Follow a trail of thermal pools in the Westfjords – an ingenious project dreamt up by architects and philosophers – focusing on the repurposing local materials, supporting communities and embracing Iceland’s natural resources.