In London, 1783, there occurred a battle of wills between the personal surgeon of King George III and the city’s most popular circus attraction, as Mark Blackmore relates

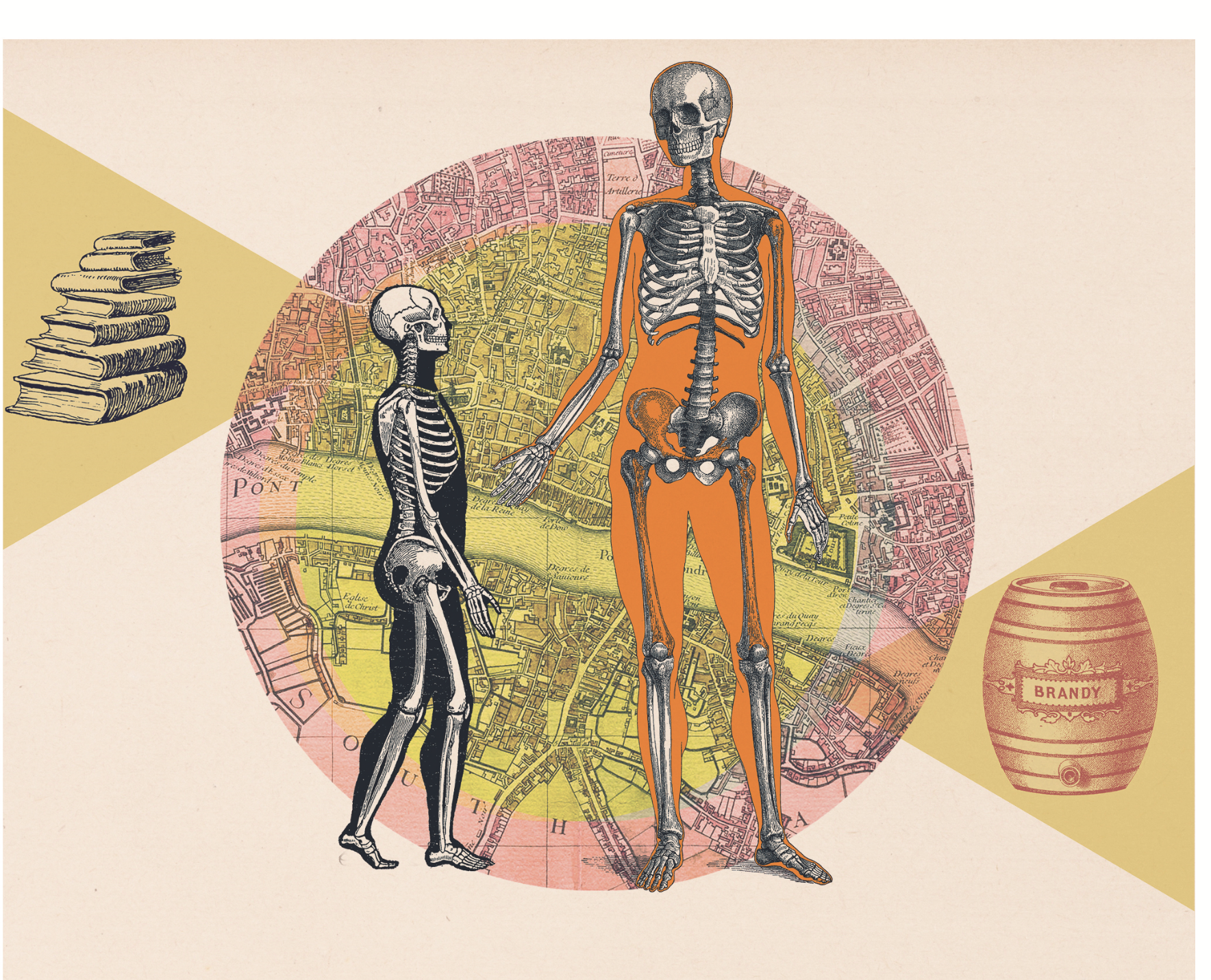

Design: Tina Smith

This is the story of two men: Scotsman John Hunter, surgeon to the king, and Irishman Charles Byrne, circus attraction. Two men from very different worlds whose paths crossed in London, 1783. Byrne, who spent his last years in terror of his body falling into the hands of anatomists, and Hunter, who was determined to be the man to dissect the Irish giant.

In 1761 Charles Byrne was born, near Lough Neagh in Ireland, to parents of average height and modest means. Here he grew up, and up and up, until he had reached a height that marked him as a giant and a ‘freak’. Over eight feet tall, according to contemporary accounts; modern science, ever the party pooper, says it was closer to 7’7”.

At the age of 19, Charles Byrne left home and began a journey that would see him become famous enough to be mentioned by Charles Dickens in David Copperfield and later used as a character in Hilary Mantel’s 1998 novel The Giant, O’Brien.

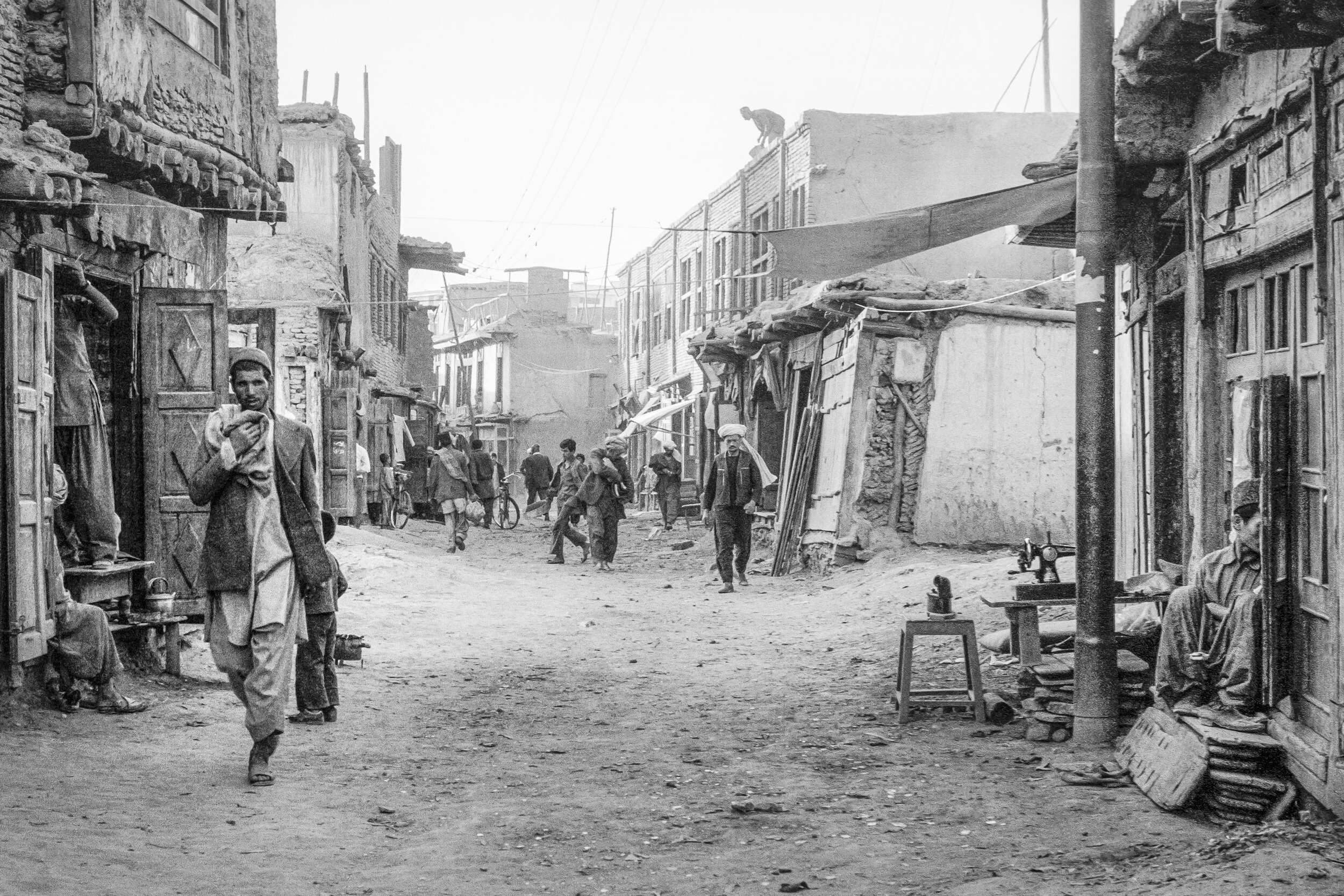

He started by touring Scotland and the north of England, promoting himself as an attraction, charging the curious 2s 6d (about 12.5p) to stand and gawp at him. By the time he reached London in 1782 his fame had spread, and he became, sadly quite literally, a short-lived phenomenon.

Byrne’s base of operations in London was Cox’s Museum in Charing Cross, an establishment set up to display unusual exhibits – Oliver Cromwell’s head was another popular attraction. Byrne lived in an apartment next door, furnished with cane furniture specially made for his gargantuan dimensions.

Byrne, however, was not coping well with the pressures of fame. It’s hard to imagine what his day-to-day existence must have been like. A person of his size, a man who could light his pipe from the gas lamps that lined the streets, could never be offstage, never blend into the crowd or cease to be the object of startled attention. On top of this, he woke from one particular night of drunken revelry to find that his life savings had been stolen from his pocket. The Irish giant, already suffering from tuberculosis and alcoholism, went into a steep decline.

He had one overriding fear. Anatomists circled Byrne like sharks smelling blood. It wasn’t until 1832 that prohibitions concerning the use of cadavers in medical research would be eased. These strict laws had caused such a demand for black-market corpses that murder was on occasion committed simply because of the victim’s resale value. In this climate, where corpses of an average size were keenly sought, Byrne’s body would be highly valued. It wasn’t that he feared being killed for his body, at least according to newspaper reports of the time. It was a morbid terror of post-mortem dissection. Byrne was the research opportunity of a lifetime, and he knew it.

The giant’s final wish

Byrne made special arrangements in the event of his death. He was to be buried at sea, so that no scientist with a shovel, a winch and a surfeit of enthusiasm could dig him up. And his coffin was to be lead-lined, just to make sure it was a tough nut to crack. He paid friends and some fishermen to ensure his wishes were respected, reiterated his burial conditions in the strongest possible terms on his deathbed, and died in June 1783 at the age of 22.

This is the point at which John Hunter enters our story. Hunter was a distinguished and accomplished fellow indeed. A Scottish surgeon and early proponent of the scientific method, he can justifiably claim credit for improving our understanding of inflammation, gunshot wounds, venereal diseases – he once infected himself with gonorrhoea and syphilis for his research – child development and most pertinently, bone growth.

Having started out assisting with dissections for his elder brother William and his brother’s former tutor, the fabulously named William Smellie, Hunter had risen to stratospheric heights in the medical profession. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1767, surgeon to St George’s Hospital in 1768, and personal surgeon to King George III in 1776. In short, this was a man whose wishes were to be respected. Even if those wishes involved dissecting the corpse of a recently deceased Irish giant who had made meticulous provisions to avoid that eventuality.

Robbed at sea

Reports on how much Hunter paid to have Byrne’s body removed from its coffin range from £130 to £500, which would be around £35,000 today. Whatever the amount, the bribe was accepted, Byrne’s coffin went to the bottom of the sea filled with rocks, and John Hunter spirited the giant’s remains away. He chopped the body into pieces, boiled away the flesh and kept very quiet about the huge skeleton in the back room. In fact it was four years before Hunter conceded that he was in possession of Charles Byrne’s bones.

Was the subterfuge justified? In 1909 an examination of the skeleton revealed that Byrne had a pituitary tumour, and in 2011 researchers discovered that Byrne had a rare gene mutation involved in such tumours. The skeleton has also proved vital in helping to link acromegaly, the overproduction of growth hormone, to the pituitary gland.

John Hunter was a difficult, brilliant man, described by a contemporary as “warm and impatient, readily provoked, and when irritated, not easily soothed”. The Hunterian Society of London was later named in his honour, and the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons houses his collection of anatomical specimens, including the skeleton of Charles Byrne.

This is where it will stay, for now. Dr Sam Alberti, current director of the Hunterian Museum, says: “The Royal College of Surgeons believes that the value of Charles Byrne’s remains, to living and future communities, currently outweighs the benefits of carrying out Byrne’s apparent request to dispose of his remains at sea.”