Welcome to the astonishing world of Muriel Howorth, Britain's very own botanical particle physicist.

Far away from the cares of Britain’s Atomic Weapons Establishment, a pantomime cow was eating a radioactive lunch. A Geiger counter flashed and clicked as the cow stood up on her hind legs, rubbed her stomach and smiled. Moments later, a balletic Atom Man pirouetted, glided across the stage then squatted before Knowledge, a figure draped in parachute silk. “The cow should soon be a perfectly healthy animal”, Knowledge said.

It’s not clear if the ballet Isotopia: an Exposition in Atomic Structure was ever seen again after its debut in the Waldorf Hotel, in the heart of London’s theatre district. Writing in October 1950, a Time magazine journalist recalled 13 members of the Ladies Atomic Energy Club gyrating across the stage in long evening gowns, as they danced and mimed the peaceful uses of the atom to a rapt crowd of 250 other women. Isotopia was one of many creations of the club’s visionary founder Muriel Howorth: script writer, choreographer, wardrobe advisor, poet, science fiction novelist, former employee of The Ministry of Information and atomic evangelist. “To lead women out of the kitchen and into the Atomic Age” was Howorth’s aim. “Not to know all about atomic energy and the wonderful things it can do is like living in the Dark Ages”.

Howorth wanted to take Isotopia to the Royal Albert Hall. She’d always been a fearless schemer, someone who knew how to marshall others’ efforts. Despite having no formal science training, she taught herself the rudiments of nuclear physics at her home in the English seaside town of Eastbourne. By 1948, she’d set up her Ladies Atomic Energy Club and was already writing to the great physicists of the time, asking them to endorse her efforts. Einstein graciously sent some encouraging words.

As early as 1949, when she presented a model of a lithium atom to a surprised mayor of Eastbourne, Howorth was staging atomic stunts in public. There was a Sunday lunch that she ate in 1959, even though the potatoes and onions were three years old. They’d been stored in the labs of Harwell, Oxfordshire, with a few grains of radioactive sodium – enough to kill any germs (and all the taste).

In 1960, Howorth embarked on her most ambitious venture. Her intentions became public when she posed for the local papers, tickling an extraordinary plant that was growing on her window sill. “Yesterday I held in my hand the most sensational plant in Britain,” wrote Beverly Nichols, gardening correspondent for The Sunday Dispatch. “To me it had all the romance of something from outer space. It is the first ‘atomic’ peanut.”

This plant had itself been grown from a remarkable peanut – a gift from Oak Ridge Tennessee (home of the Manhattan Project). Like Howorth’s onions and potatoes, this peanut had been irradiated. In this instance, all that atom blasting had done something extraordinary: it had disrupted the DNA of the peanut to create a mutant – a peanut that would grow into a giant plant, one with nuts as big as almonds. The plant itself wasn’t radioactive – its crop tasted good and was perfectly safe to eat, just like any other peanut.

In praise of the mutant vegetables

With food rationing in Britain still a recent memory, it’s no wonder Howorth was drawn to the implications: take a large batch of seeds of wheat, barley, tomatoes or another foodcrop – irradiate them and, if you’re lucky, you will make some mutants. Some of those mutants might grow in odd colours, some might grow tall or twisted, others will wither and die. But if you’re lucky, you may find that one in a billion mutation: a plant that grows large enough to end world hunger. With her leadership, Howorth was sure the gardeners of Britain could work together to find this golden mutant.

Howorth instructed her husband Major Howard to set himself up as the sole European distributor of atom-blasted seeds from Van Hage Company, Holland. She also persuaded Harold Wootton to exhibit her specimens in his Wonder Gardens, a pleasure garden in Wannock, a few miles outside Eastbourne. Thus her experimental, atom-blasted allotment was visited by thousands of families on Sunday afternoons on their way to the model village and tearooms.

Howorth opened the doors of her Atomic Gardening Society and asked for willing amateur gardeners to join her. This was citizen science on a grand scale, all handled through the Post Office. All you had to do was request some atom-blasted seeds from The Major and buy Howorth’s book, Atomic Gardening for the Layman, to jump into the atomic age.

Seeds were posted to volunteers, along with instructions on how to nurture them, log their growth and report back on any interesting mutants. Finding the golden mutant was a game of chance. Every volunteer and every new planting improved the odds of finding the plant that could, in Howorth’s eyes, save humankind. The odds, however, were stacked against her. Howorth managed to recruit around 300 gardeners – but a thousand times that number would be needed to have any likelihood of creating even a handful of mutations, let alone the giant plant she longed for. To encourage the gardeners’ competitive spirit, Howorth announced the most promising mutant each year would be awarded the “Muriel Howorth Peanut Prize”. We don’t know if anyone ever took home the trophy. Despite her optimism, by the mid-1960s, the volunteers had little to show for their efforts. The Atomic Gardening Society quietly fizzled out.

By this time, many plant scientists had abandoned atom-blasting, seeing it as a haphazard way to find useful mutants. They turned their attention to chemical methods of splicing the gene - techniques behind the GM crops of today. As atomic gardening historian Paige Johnson said to amusingplanet.com. “If you think of genetic modification today as slicing the genome with a scalpel, in the 1960s they were hitting it with a hammer”. Howorth never reconciled herself to this, clinging to the romance of the atom until her death in 1971.

As an atomic pioneer, Howorth was a visionary. Although she never found her giant mutant, in many other ways, her work was a triumph. Decades before the era of crowd sourcing, she demonstrated that anyone could set up and run their own scientific experiments, following their own interests rather than the agenda of established laboratories. Long before anyone had ever spoken about open source culture, she was already sharing scientific knowhow for the price of a few first class stamps.

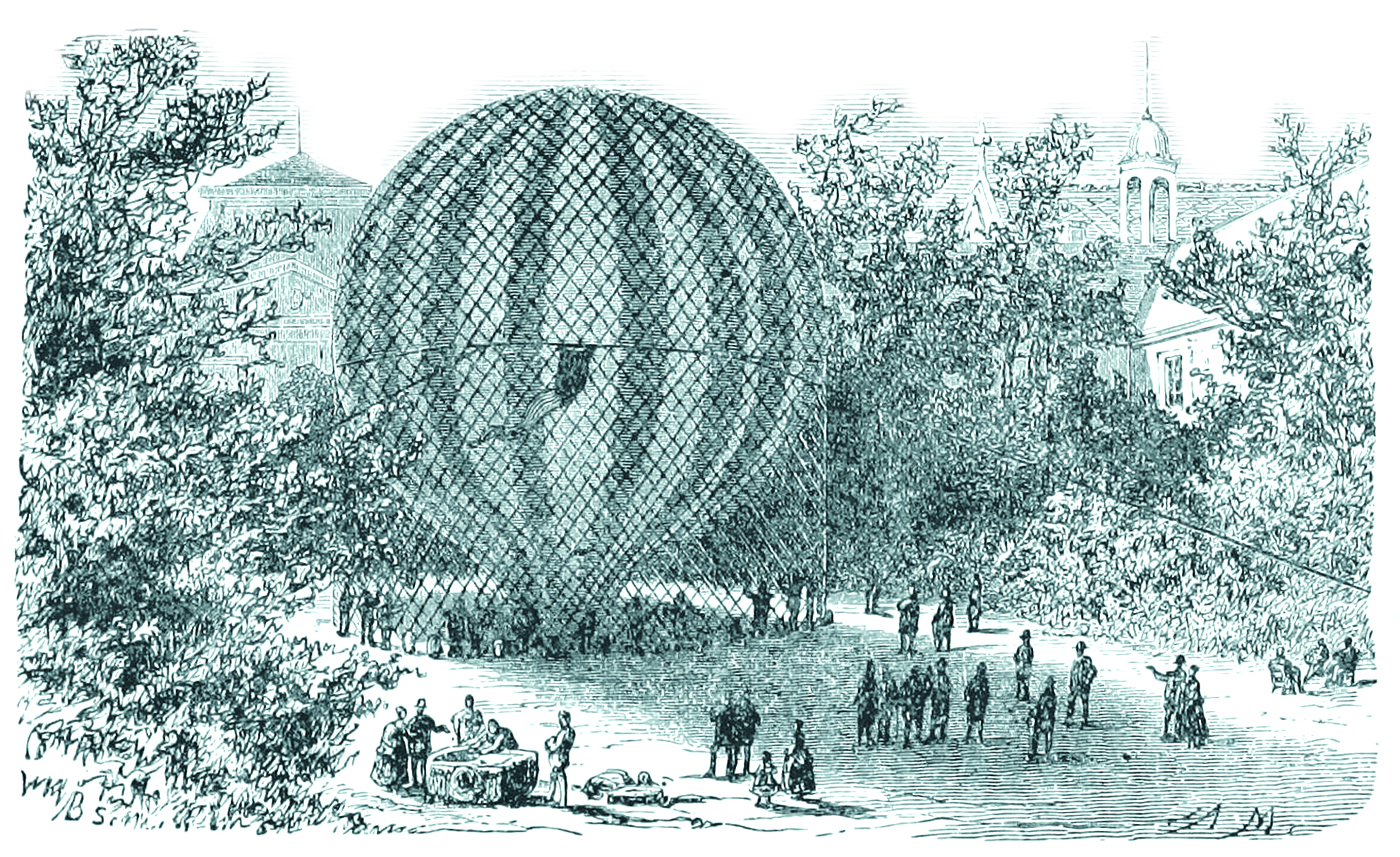

Howorth would be delighted to know that atomic gardening is making a comeback. In tightly controlled experiments, crop scientists are growing plants in circular fields that are continually bathed in radiation. This comes from highly radioactive cobalt-60 – a source so deadly, it has to be dropped into a lead-lined sarcophagus before anyone can enter the field. Rapid genome testing lets them sift through thousands of results. In Atomic Gardening for the Layman, Howorth hinted at plans for her own cobalt-60 garden, something she never had the funds to bring to fruition.

Howorth didn’t have the chance to study atomic science formally, yet she came up with experiments that were rationally designed and breathtaking in their ambition. She achieved so much on that windowsill in Eastbourne, in Slaymaker’s Wondergarden and in the pots of atomic gardening pioneers around the UK. Just think how much more she could have done if she’d been given the keys to the lab.

Words: Sarah Angliss