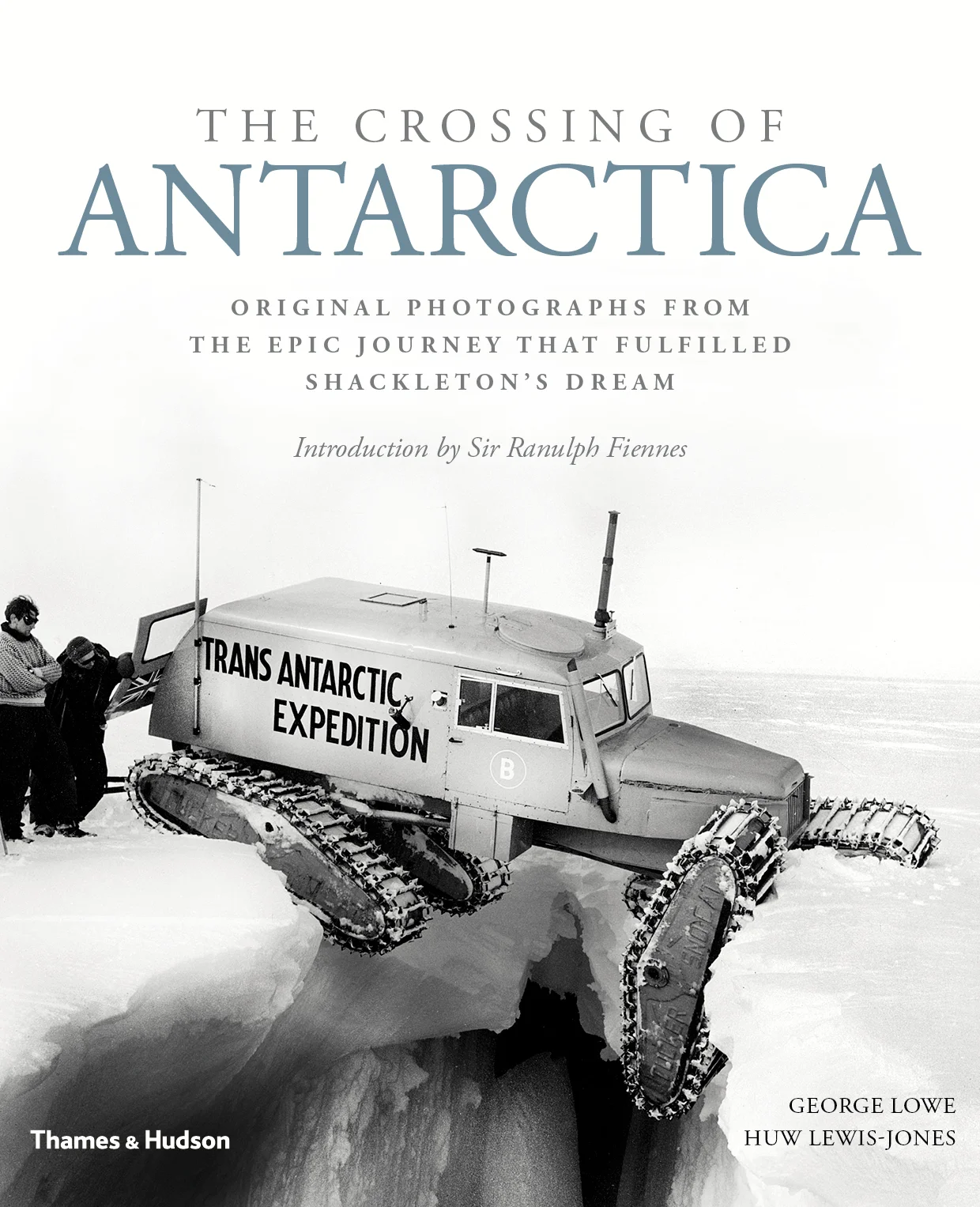

One hundred years after Sir Ernest Shackleton set out on his ill-fated attempt to cross Antarctica, this book celebrates the expedition that succeeded where he failed. Thom Hunt of 7th Rise and Channel 4's Three Hungry Boys shares his thoughts on The Crossing of Antarctica.

Fierce winter winds carved a gully behind the hut at Shackleton © The George Lowe Collection

In a world saturated by health and safety regulations, hedging your bets and insurance for every possible scenario, this book smashes through wary modern thinking like a freight train on its way to unexplored corners of the world.

The Cross of Antarctica tells the story of the 1957-58 expedition led by Vivian ‘Bunny’ Fuchs – an epic journey that fulfilled Shackleton’s dream and became one of the 20th century’s triumphs of exploration, a powerful expression of human willpower.

The book comes from a time when men were men, with beards and dexterity; men who could fix almost anything and would laugh in the face of a blizzard. The photography – sourced from the private archives of Everest veteran George Lowe as well as items from the Fuchs' family collection – is mind blowing and the words and interviews a mixture of poetry, philosophy and downright bluntness. And why wouldn't they be? These chaps had been there, done that and gone back for more.

I, for one, am thankful that these stories and photos have been discovered and published but I guess the last real test is this: if we read such tales of courage and determination then we close the pages only to remain stagnant, I believe we are doing a disservice not only to ourselves but also to these great men of adventure. Greatness is not reserved for the few enlightened ones, it is available for each and any of us who commit to advancing towards the unknown. This book taught me, just when I needed it, that the extraordinary is but a decision away.

If life is as adventurous as you want it to be then it ain't broke, so don't fix it. But if thoughts lurk in your mind of a life less ordinary, buy this book, read it, then see how far the rabbit hole goes.

Star rating: 5/5

Reconnaissance foray on the Skelton Glacier, 1957 © The George Lowe Collection

© The George Lowe Collection

© The George Lowe Collection

George Lowe taking a portrait of a penguin © Jon Stephenson

© The George Lowe Collection

© The George Lowe Collection

Vivian ‘Bunny’ Fuchs’ Sno-Cat Rock’n’Roll becomes jammed nose first in the far wall of a deep crevasse © The George Lowe Collection

© The George Lowe Collection

© The George Lowe Collection