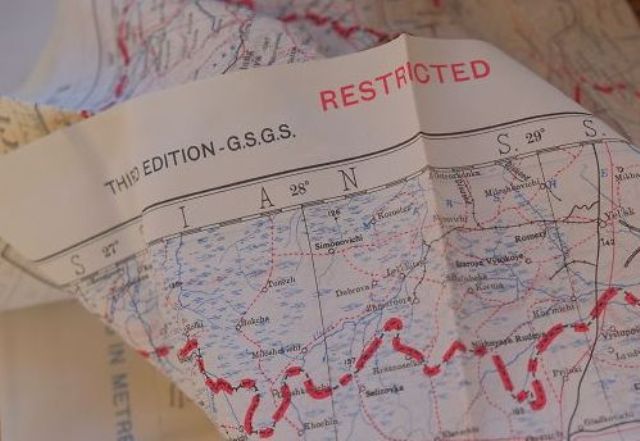

August 1914: Europe descends into what will become a long and bloody war. Days later, after being given the order to proceed by Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, Ernest Shackleton and his men set off to cross and conquer the Antarctic.

Portrait of Ernest Shackleton, © National Maritime Museum, London

The expedition consisted of two ships, Endurance and SY Aurora. Meeting Endurance in Buenos Aires, Shackleton sailed with his men to the Weddell Sea, to begin their march via the South Pole. The Aurora sailed to the Ross Sea, on the other side of the continent, ready to set up supply depots along the route to the Pole, supporting the men of the Endurance on their trek and undertaking scientific research.

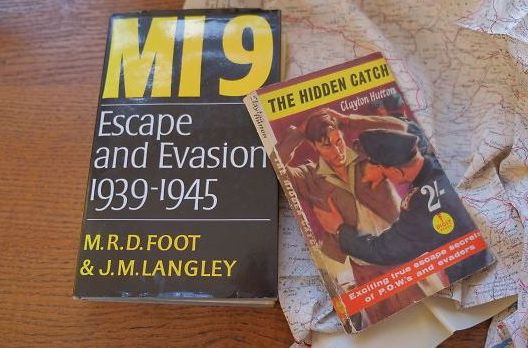

Things did not go according to plan. By early 1915, Endurance had become frozen in pack ice. The crew camped on the drifting floes for months, salvaging what they could before the ship finally sank to the icy depths in November. Below are some items rescued from the expedition.

Leonard Hussey's banjo

© National Maritime Museum, London

When the men abandoned ship, they were only allowed to take minimal possessions with them. The exception was this: the meteorologist Leonard Hussey’s banjo, which Shackleton called “vital mental medicine”, crucial to maintaining morale. They kept it with them as they made a five day journey in the ship’s lifeboats to land on Elephant Island.

Marine chronometer

© National Maritime Museum, London

From the remote Elephant Island, Shackleton decided to launch a mission to get help. He and five others set off in the James Caird lifeboat, hoping to reach the whaling station at South Georgia, some 800 miles away. The men were reliant on Frank Worsley’s navigational skills in heavy winds and rolling seas. This chronometer was probably used on their epic voyage.

Liquid boat compass

© National Maritime Museum, London

It is likely that Worsley used this liquid boat compass for navigation on that horrendous trip. The men had to continuously bail water and chip ice from their leaky boat in freezing conditions. They finally made landfall 16 days later. The exhausted Shackleton, Worsley and Crean then had to traverse mountains and glaciers to finally reach help.

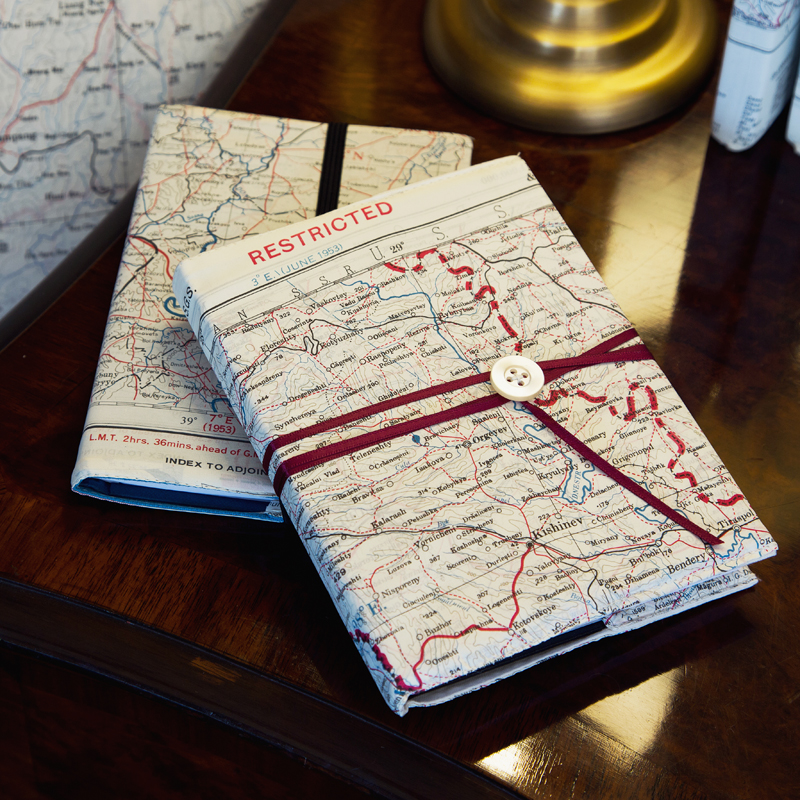

Victor Hayward’s Journal

© National Maritime Museum, London

On the other side of the continent, things had also gone awry. In May 1915, Aurora was carried out to sea, stranding 10 men without much of their equipment, food and fuel. They continued to lay depots for the anticipated continental crossing, although hungry and weak. Three died. Victor Hayward, one of those men, last wrote in this journal two days before he disappeared following a blizzard.

The men on Elephant Island were rescued in August 1916; the remainder of the Ross Sea Party in January 1917. Shackleton and his men finally returned to find the world still in the midst of war. Many of them served in the conflict. Shackleton returned south once more, but died in South Georgia in 1922, and, according to his wife’s wishes, was buried there.