Whether used for impressing a mate, cracking open nuts or proclaiming territory, bird beaks are a prime example of how anatomy has evolved to be completely fit for purpose. Here we look at the beaks of British and migratory birds, and their unique specialisations for survival

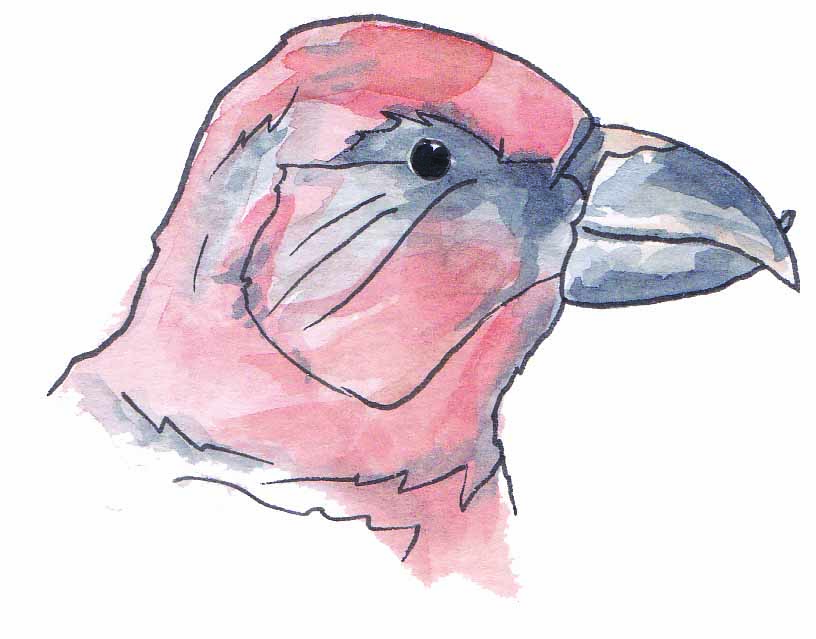

Puffin, Fratercula arctica

Its bill has earned it the nickname 'clown of the sea', but once breeding season is over, the puffin sheds its characteristic bill, leaving a duller, smaller one behind.

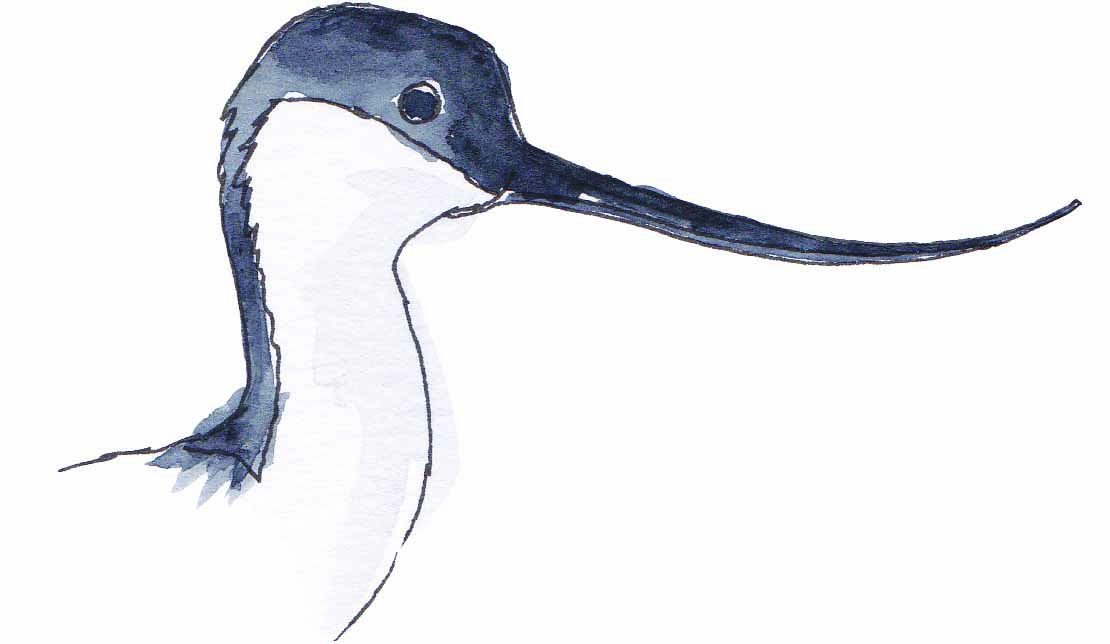

Avocet, Recurvirostra avosetta

Emblem of the RSPB, this black and white wader employs a sweeping action with its long, thin upturned bill to stir up small invertebrates to the water’s surface, then it uses its beak like tweezers to pluck out its prey.

Crossbill, Loxia curvirostra

To break into larch or pine cones, crossbills have evolved powerful bills with crossed tips, which prise off the woody scales of each cone to extract a seed.

Hawfinch, Coccothraustes coccothraustes

Its bill exerts 68kg of force per square inch – enough to sever a human finger and crack open a cherry stone with one swipe.

Great spotted woodpecker, Dendrocopos major

To sound its territory, a woodpecker uses its beak to strike wood 15 times a second with force equal to a human hitting a wall face-first at 20 miles an hour.

Spoonbill, Platalea leucorodia

These elegant water waders use their long, spatulate, partly-open bills to swing from side to side in the water, stirring up mud and debris. When insects and small fish touch the side of its bill, it snaps shut, trapping the prey inside.