Thank you for pre-ordering, subscribing and for your patience, dear reader! Once the ink has dried, issue six will be on its way to you. Read on to explore a few of the themes playing out in this edition: stories of shelter, etymology and the strange and wonderful things that can happen when you delve into old journals and archives.

In the summer of 1956, Jack Kerouac spent 63 days manning a fire tower on Desolation Peak in the North Cascades. Other than penning a letter to his mum, scribbling journal entries and composing the odd haiku, he didn’t get much done; he spent his days brewing coffee over a handful of burning twigs and watching the clouds roll by through the lookout’s panoramic windows. In Lonesome Traveller, published four years later, he describes his yearning for solitude: “No man should go through life without once experiencing healthy, even bored solitude in the wilderness, finding himself depending solely on himself and thereby learning his true and hidden strength.”

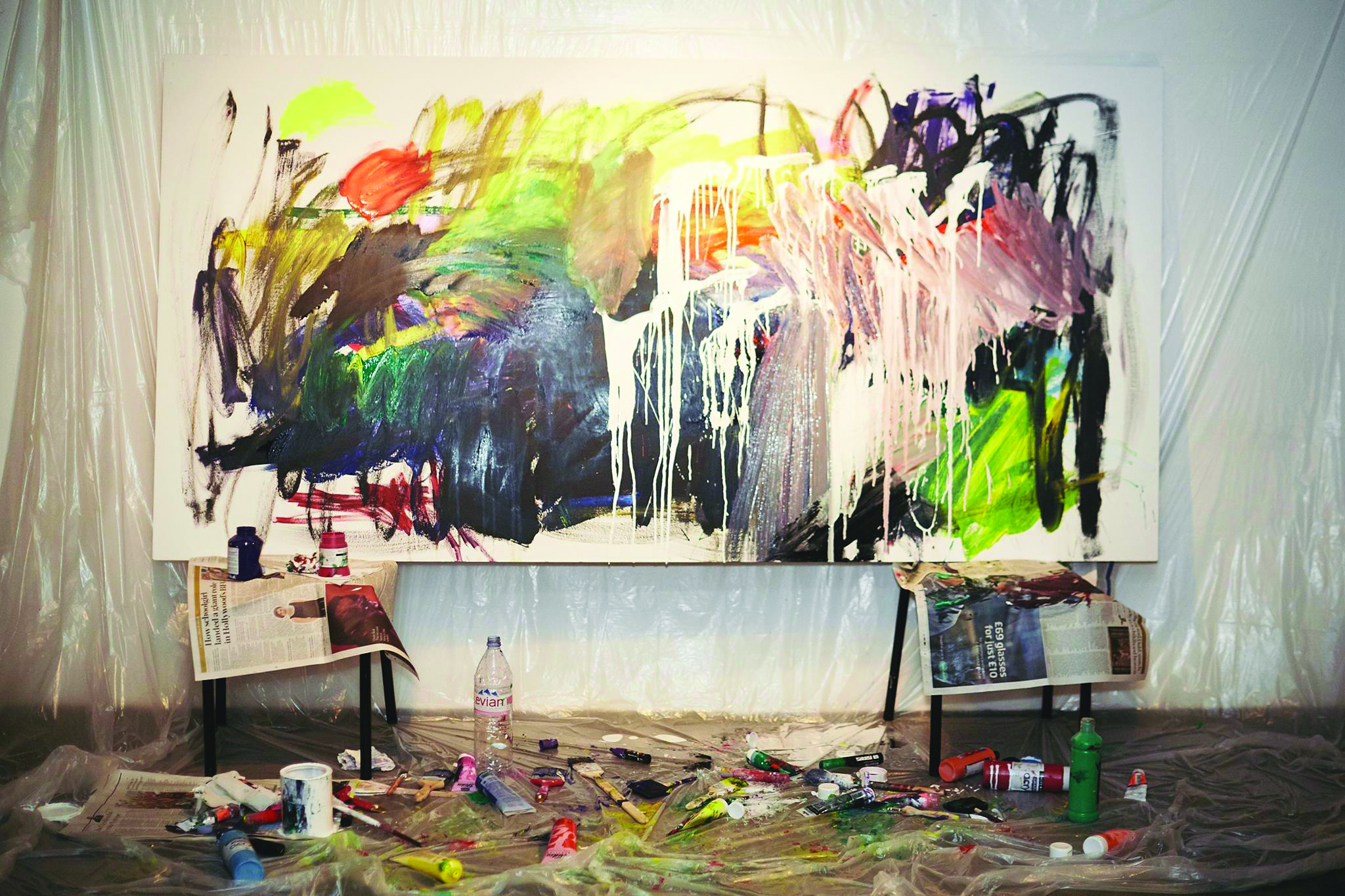

Whether a refuge at the ends of the earth, a base for scientific research or a sanctuary in which to write (or – in Kerouac’s case – to just be), functional shelters have an irresistible allure. They present a space in which we can understand ourselves. In his article ‘Gimme Shelter’, author Dan Richards uses these basic structures – cabins, bunkers, eyries and bivouacs – as a lens through which to examine our relationship with isolation, wilderness and creativity. While in ‘Hole & Corner’, artist Luke Franklin leads us on a merry chase across Ireland in search of hidden bothies: four simple sheds built for creative folk to use freely and kept secret by a non-disclosure agreement with a post-apocalyptic clause.

As well as investigating ideas around shelter, in issue six we also examine the strange and wonderful things that happen when you burrow into old journals and archives. Starting with a personal obsession, we follow in the wake of Charles Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle by seeking out the curious human and natural history stories of the Galápagos Islands – a volcanic archipelago the naturalist described as “eminently curious”. Meanwhile, Huw Lewis Jones and Kari Herbert delve into explorers’ sketchbooks that changed the way we see the world. James Burt surveys superhuman feats of memorisation and explains how to construct a memory palace in which to store your most precious thoughts. Finally, Bethan Stevens and George Mind share their experience archiving the work of 19th-century engravers, the Dalziel Brothers, during which the team became so immersed in their research it seeped into their everyday lives.

Meanwhile, it wouldn’t be an issue of Ernest if we didn’t explore an obscure tale of etymology. So, after learning some seafaring vernacular, why not join writer Joly Braime as he roots out the origins of a long-lost Nordic language found hiding in the North York Moors?