Drawing inspiration from 18th-century collectors, Elisabeth Pellathy's latest work explores themes of conservation and preservation. Recently showcased at the ONCA Gallery in Brighton, Visualised Bird Song explores an innovative method of preserving sounds disappearing from our natural world. Matt Iredale caught up with Elisabeth Pellathy to talk translation.

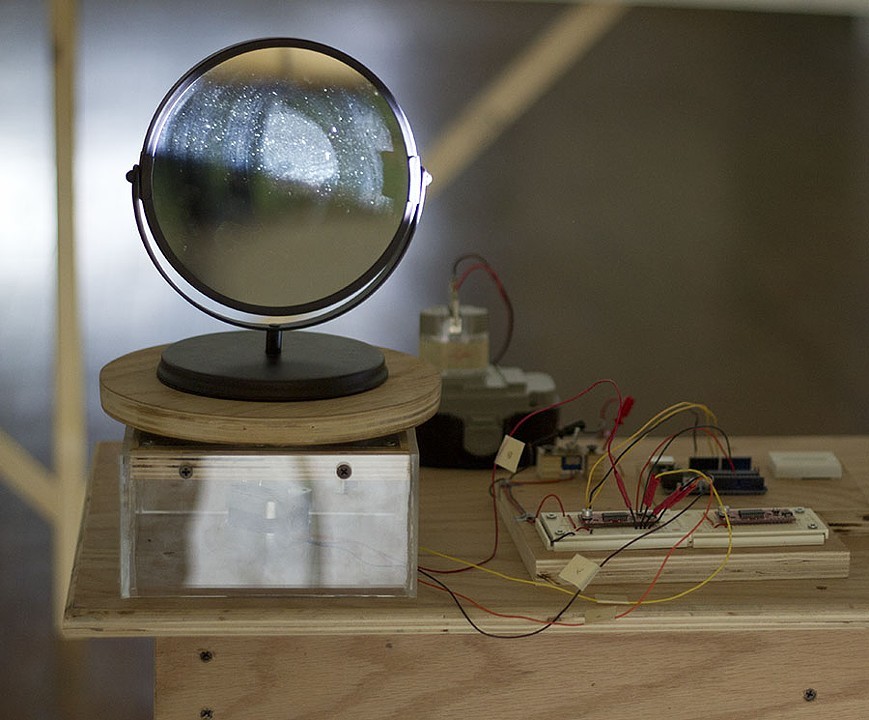

When we hear the sounds of morning birdsong, we seldom think of it as something disappearing – or that it might be possible to hold in our hand – but these thoughts are integral to Elisabeth Pellathy’s new exhibition, Visualised Bird Song. As a professor of New Media at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Pellathy’s art encompasses a variety of techniques, ranging from 3D printing to lithography. As a result of her exhibition at ONCA, Visualised Bird Song is soon to be displayed at Brighton and Hove’s Booth Museum of Natural History.

Where did the idea for Visualised Bird Song originate?

It originated in two places. Firstly, I was listening to Peter Cusack’s work, Sounds from Dangerous Places. Cusack’s recordings highlight the vibrancy of life - be it human, insect or bird - in politically dangerous or environmentally damaged locations. My second source was Melody Owen. She was about six years ahead of me in graduate school and she makes these beautiful birdsong chandeliers. They are quite large and have a different quality to my work. I was thinking more about 18th-century taxidermy, collection and ‘wonder cabinets’. I wanted to infuse the bird song with this idea of preserving moments in time.

Preserving the ‘disappearing’ has been integral to a lot of your work over the years. Could you tell me more about the issues that you are trying to focus on?

I don’t want to clobber people over the head. The idea that ‘if you use plastic you're the enemy of the environment’ often ends that conversation. What I’m trying to say, hopefully, is that through technology and communication we can be empowered to think about endangered species and the environment more critically. Maybe there will be some animals of which you've never heard, but seeing them on a timeline will show you what’s still there and what’s not. It’s the same with indigenous languages. Maybe not to the daily speaker, but they embody a long history of expectations, sounds and humour.

The homogenisation of language and culture is an important issue today. Is translation and conversation at the heart of your work then, or is it based in nostalgia?

I love translation. When you do a 3D print the file format is an STL (STereoLithography). This file format was invented by Charles Hull, who created the first SLA machine in 1983, later this file format was patented in 1986 and when that happened it democratised 3D printing as an industry standard, opening up new avenues for everybody. It’s actually made up of hundreds of triangles. So, I took the ready to print STL file and put it back into the software to make the 2D prints.

I have a problem with nostalgia. I have no nostalgic memories for these birds. I’ve heard them, but I’ve never done my own field recordings or seen them. There is a disconnect. I think my work is about forming a connection with something that you would be unable to experience, like in a natural history museum. You look at a cross section of time in the glass cases and are blown away. It’s about the poetic slippage of natural history and art, and forming a dialogue. I think crossing timelines through the discussion of the 18th-century collector of curiosities is more appropriate. At the time, those people were conservationists, leading voices in the categorisation of natural history.

Has your social position as a first generation American influenced your work?

I think this was the catalyst for preserving the rapidly disappearing because both my parents are Hungarian. My parents immigrated to the United States in 1946 and 1951, respectively. My grandfather was actually working for the Hungarian government as a naturalist, categorising mushrooms and wild edible foods. I think that’s where this idea of preservation comes from. People ask why I don’t use my family’s story as a more direct inspiration for my work. I say that’s what has made us, it’s our heritage, but it is not necessarily what I want to dig into with my art. I take the idea of my family and then move it 5 degrees.

Can you tell me about the ornithological theme that pervades your work?

[She laughs] I’m going to be that crazy bird lady. I try and move my work away from it and I always come back. I went to China for an installation. I had this huge space that I could do whatever I wanted with and I ended up printing birds - 9ft banners of extinct birds! When I drive to work, I think I’m going to do something new, but I just keep coming back to birds. Maybe I could do something on insects; I mean they fly too. But I have a one-track mind. I’m a birdbrain.

Well, the one place birds don’t appear is your collaborative work with Lee Somers, could you tell me more about the SanLun Yishu project?

We were living in China at the time. The SanLun Yishu are three-wheeled vehicles made for short journeys from the store to your home. Funded by BlackRock Arts Foundation, we renovated one, so people could get a free ride and an art exhibition. Inside, we had prints and a video playing. It was a kind of reprieve from the busy Beijing streets, which was the initial catalyst, as it is very hard to find any sense of peace in the city.

Do you still have the SanLun Yishu?

I wanted it but when we returned from China, our luggage was too heavy. I put everything I could from two years in there, including lots of rocks from the edge of Western Tibet.

Did the SanLun Yishu project influence your later work in any way?

Not really, it was a project that we did and then we went our separate ways. He’s a ceramicist and I’m a digital artist, although he’s my partner we got tired of each other; [she laughs] I mean artistically. I’m sure he would have a much kinder take on that. We’ve collaborated since. We did a show in August of 2016 on landscapes and the environment, which went really well, but artistically we did our separate works and then came together, rather than one big project. Lee and I have now been invited to participate in another collaborative project with artist Scott Stephens at The Institute for Electronic Arts - a research studio facility within the School of Art and Design, NYSCC, Alfred University, New York.

The homogenisation of language and culture is an important issue today. I mean language literally changes the structure of one’s brain, which is quite a tactile idea. Considering the techniques you have used in many of your works, is there a desire to engage with concepts that are more tactile and tangible?

I think it’s just my training. I’m a professor of New Media, so I teach film and animation, but I used to be a print maker. At heart, I draw. It’s where art started for me, so that tactile experience translates to all of my work. I regularly scratch onto 16mm film and I even do rotoscoping. I think the hand mind aspect is very important to me as an artist, I don’t think it was an intellectual choice. I do a lot of stuff on the computer, but having the result from digital translating to analogue is a beautiful conversation.