If you think your current 9-to-5 is a bit of a drag, spare a thought for the poor souls who had to do these foul-smelling, back-breaking and often downright dangerous jobs. Whether through technology, health and safety or social enlightenment, these professions are, thankfully, now a thing of the past.

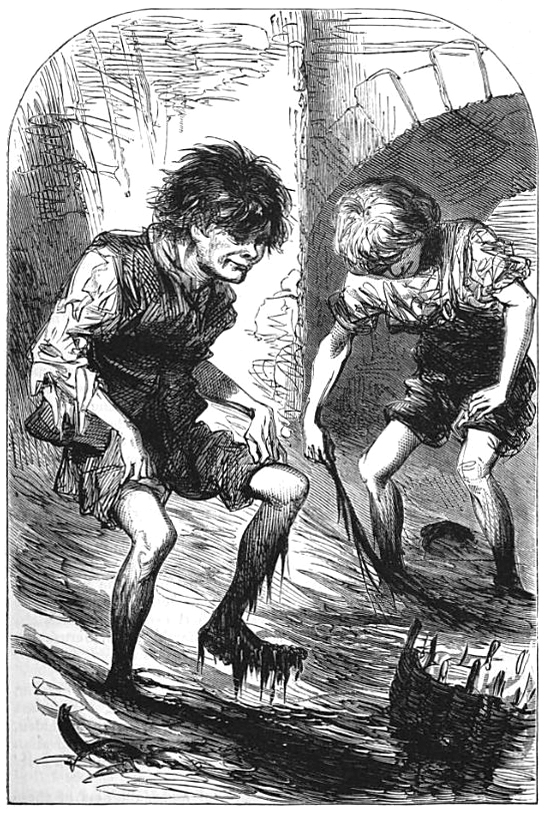

Image: Mudlarks of Victorian London (The Headington Magazine, 1871)

gong farmer

In Tudor times, gong farmers had the delightful task of emptying cess pits and privies of human excrement – or ‘night soil’ – and transporting it outside the city. They only worked at night and had to live a fair distance away from others so as to minimise the chances of spreading any nasty diseases they may have picked up. And because, frankly, they stank.

herb strewer

Before there were sewers, there were herb strewers. But they only worked for royalty. Dating back to the 17th century, the strewer’s job was to scatter sweet-smelling herbs and plants throughout the royal apartments to disguise the stench emanating from the Thames. When trod underfoot, the herbs would release their aromas to ensure royal noses remained unsullied.

mudlark

A mudlark was someone, usually a child, who scraped a paltry living by scavenging in the mud along the low tide line of the RiverThames. Working among raw sewage, excrement and the occasional corpse, they’d gather up bits of iron, rope, copper and coal that had fallen into the river – although the more daring would also pilfer from passing barges.

knocker-upper

During the Industrial Revolution, early shifts were the norm at factories and mills, but most people couldn’t afford alarm clocks to get them up in the morning.To ensure the workforce arrived on time for their daily toil, a knocker-up was employed to tap, tap, tap on the bedroom windows of the sleeping workers using a long stick, until they were roused from their slumber.

legger

Early canal tunnels were narrow and didn’t have towpaths.The legger’s job was to walk or ‘leg’ the vessel through the cold, dark tunnels.Working in pairs, lying on planks attached to either side of a boat, they navigated through tunnels up to a mile long. Physically demanding and highly dangerous, it was common for leggers to come to grief and be crushed between the hull and the tunnel wall.