Dean Hearne, creator and curator of The Future Kept talks to jewellery maker Abigail MaryRose Clarke about upcycling beautiful objects that have outlived their intended use

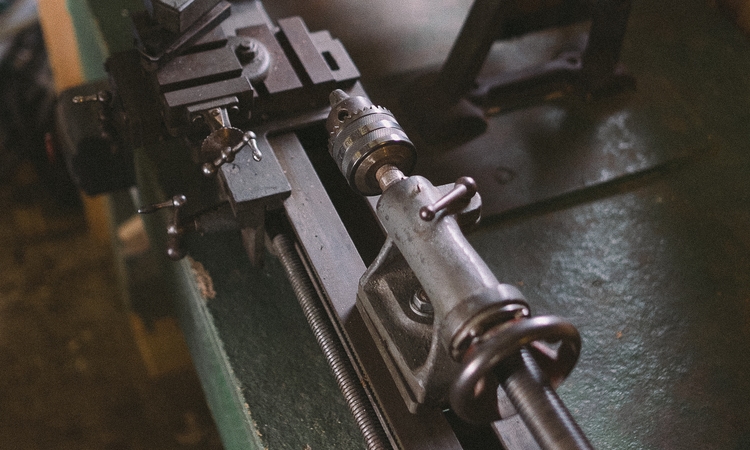

SGMR's tools of the jeweller trade

What first got you interested in making jewellery?

As a teenager I wasn’t impressed with the mass-produced accessories that were available on the high street. My school friends and I would venture to an old junk shop in the Brighton laines that had vintage jewellery from all over the world. In school I started to make my own jewellery from whatever I had lying around and I continued my experiments through college and university.

Tell us about your design style – what makes your collections unique?

I love to work with patterns, glazes and texture so I tend to find a ceramic piece and try to incorporate the existing image or design. I like to preserve the original qualities and history of the piece rather than just smashing up a plate to use the shards.

Where do you draw your inspiration from?

I am obsessed with ceramics in general, from contemporary designs to chintzy antiques; Scandinavian, West German and Postmodern ceramics always catch my eye. Most recently, 1960s and 70s British ceramic designers have played a huge part in my work, especially the work of Susan Williams Ellis of Portmeirion and Honor Curtis of Troika, St Ives. I love their techniques of the way they combine embossed symbols, scratched patterns and organic rough glazes. There are some incredible modern ceramic artists I follow on social media, such as Martina Thornhill, B-Zippy and Young In The Mountains.

What did you do before you made the leap into being a full-time jewellery maker?

As a student in Manchester I'd work part time in bars and music venues in the evenings and at weekends. I eventually ended up moving back to the south east where I ran an old bookshop and crafted in my spare time. I then started to apply for craft events and created an online Etsy shop. The big change came when my work was spotted by the accessory buyer at Anthopologie and everything started to take off.

Can you tell us about a favourite piece that you have created?

I love giving my jewellery to friends and family – this was originally who I started making for. I particularly enjoyed designing the groomsmens' button holes for my friend's wedding as well as the bridesmaids' head pieces for my brother’s wedding. It’s always an honour to be asked to make a piece for such a special occasion.

What are your favourite places for sourcing materials?

Oh there are so many! When sourcing for larger wholesale orders I go to the larger porcelain manufacturers in Stoke-on-Trent to buy in bulk. It’s always so amazing to look around the old pottery mills and factories – some still have the old kilns and equipment lying on benches, and old plaster moulds and bisque-ware stacked on drying racks. For smaller-scale orders and commissions I look around charity shops and markets. I adore Lewes flea market and the old fishing hut antique shops in Rye, but I absolutely love it when the customer brings their own heirloom crockery to be transformed. I've recently finished an order for a bride-to-be, using her grandmother’s wedding china. That really makes the transformation all the more special.