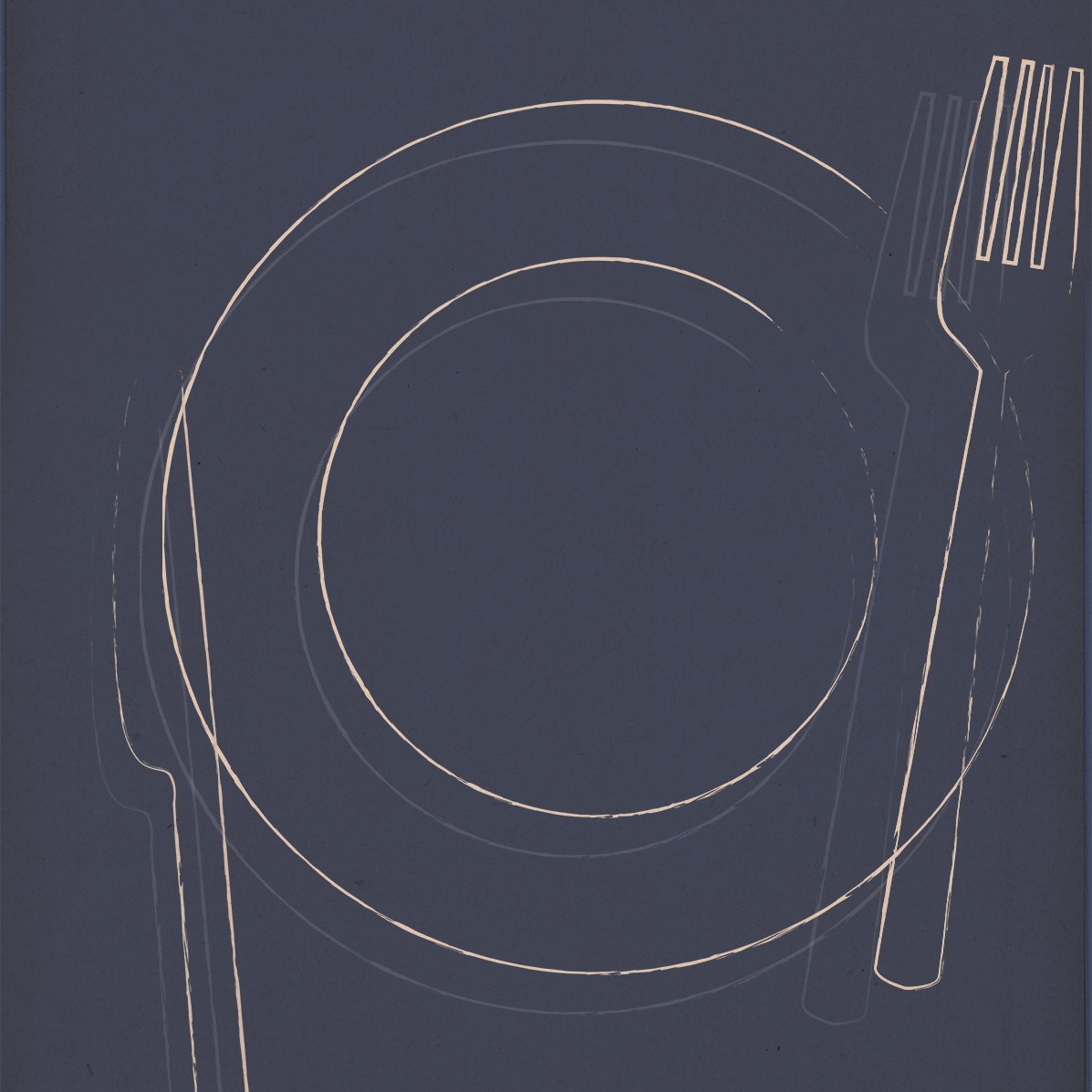

Dans Le Noir means ‘in the dark’. Put simply; a restaurant with no natural or artificial light, where you eat in pitch blackness, served by waiters who are blind or visually impaired. The idea is to intensify your other senses through limiting the sense of sight, to gain a new perspective of the food you eat while also raising awareness of visual impairment. This concept of ‘dark dining’ or ‘blind dining’ was founded in Paris in 2004, and since then other Dans Le Noirs have popped up in London, Barcelona, New York, St Petersberg and Kiev.

After hearing it praised by the illustrious Stephen Fry on an episode of QI (a source of most of my knowledge and trivia), I took a friend along one winter’s eve, excited and anxious at the prospect of entering a pitch dark room full of strangers and cutlery. We were greeted in the (lit) reception area by our blind waiter and guide Darren Paskell. We chose from four secret set menus – Surprise, Meat, Fish or Vegetarian – which gave no other indication of what we were going to be served later. I opted for the Surprise menu.

We were asked to put all bags, coats and other trip-up-ables in a locker along with our mobile phones and luminous watches. “It’s amazing how many diners are reluctant to give up their phone, “Darren told me. “But that’s the beauty of Dans Le Noir; you sit and eat with your friend or partner with absolutely no distractions, just each other.”

Darren then placed my hand on his shoulder; instructed my friend to do the same on my shoulder, then he led us from the lit world through two black curtains into the dark world.

“Has anyone ever freaked out at this bit?” I asked him as we passed through the first curtain. “Yes, my mum,” he replied. “She’s very claustrophobic. We got past this first set of curtains and my mum just said “No, I can’t go any further.” I had to take her back to the lounge where she was kept happy with wine. My dad went in and had his meal, though.”

Into the darkness

After the second curtain, that was it – I couldn’t see. I waved my hand in front of my face. Nothing. The first thing that struck me was the noise. It was like walking into the London Stock Exchange with the lights turned off. I don’t know whether losing the power of sight instantly makes you elevate your voice but it was certainly the case in Dans Le Noir’s dining room, laid out before me like a black and noisy void. As we were led to our table I felt the draft off waiters walking past, heard the clattering of cutlery and exclamations of “Cous cous – that’s definitely cous cous”, “I’ve just spilled my water!” and “Sorry, that was my leg”.

Darren seated us at what felt like a marble table, and gently guided our hands to show us where our cutlery, wine glasses and other dining paraphernalia was. I asked him about the layout of the restaurant. “The restaurant seats 60 people altogether and the layout of the tables never changes, otherwise things could get very confusing,” Darren’s voice, just above my head, sounded louder and deeper, almost of a late-night radio DJ quality. “Each waiter carries a walkie-talkie so we’re all in constant contact with each other and the kitchen.”

He then explained some of the slick and efficient procedures put in place to ensure each diner is given the correct plate of food. “Most of the food is served on square plates but any special dietary requirements are served on round plates so the waiter doesn’t accidentally give it to someone else.”

A guessing game

My first plate of food arrived and I gingerly gave it a prod with my fingers. Some sort of raw fish on a mound of something herby and grainy. “Salmon,” I declared triumphantly, after a mouthful. “No, it’s tuna,” a voice piped up next to me. We were sat next to a couple on a blind date (a common thing for diners to try at Dans Le Noir), one of whom was eating the same starter as me. Before I knew it, a conversation about taste and texture and other madcap dining experiences was struck up with these faceless strangers, which I doubt would have happened so freely and easily if we were eating in a normal lit restaurant obstructed by social barriers and conventions.

My main course was the most puzzling to fathom – I couldn’t work out what meat I was chewing. It was beefy, so I left my guess at that. I discovered later, when our menus were revealed to us back in the lit lounge area, I was very wrong. I won’t tell you what the meat was as I don’t want to spoil the surprise. Let’s just say it’s a stripy animal often found on the savannahs of Africa.

Darren joined us for a drink after the meal and apologised for tripping over a chair next to me when he was serving my dessert course earlier. I hadn’t noticed at the time. “I think my spatial awareness is pretty outstanding, if you don’t mind me blowing my own trumpet. I’ve only ever spilled something over someone once, which wasn’t my fault or theirs. They unwittingly put a glass of water smack bang in the middle of the table.”

I asked him what he enjoyed most about working here. “The interaction. Having fully sighted people putting their faith and trust in you. In most restaurants the waiter is there to be seen and not heard – they’re expected to deliver the correct meal to the correct person and that’s about it. Here, we’re guides, not waiters. People open up and want to know more about us. In a normal situation you might come across a blind person walking along the pavement and that’s it – there’s no time or call for interaction.”

Stripping it back

While the food wasn’t exactly boundary pushing (although my main course was certainly a surprise), the experience of sightlessly pouring myself a glass of water and sharing a meal with an old friend with nothing but the sound of our voices was stripping social interaction back to its bare essentials. No phone. No visual distractions. No judging on appearance. Dans Le Noir is the perfect place to shed your skin and just be yourself, or perhaps even be someone else for the night if you wish.

As we were leaving, I spotted a couple sat at a candlelit table in the corner, looking rather engrossed with each other. I wondered if they were the blind date people I’d chatted to in the dark earlier. Maybe. I thought it best to leave it a mystery.

Dans Le Noir, 30-31 Clerkenwell Green, London EC1R 0DU

london.danslenoir.com

This featured in our fifth digital edition of Ernest Journal, available to download now.