As a natural history enthusiast and founder of Eastern Biological, Alfred Addis is no stranger to studying exotic creatures – but embarking on a drawing class with real life reptilian models is definitely a step outside his comfort zone.

A model lizard from the Wild Life Drawing class.

It’s a sobering thought, how over the centuries the urban human has removed his or herself from the natural world. Buildings grow taller and towns spread wider. City dwellers complain of rapid development whilst simultaneously trying to rationalise why they choose to live this way. Do we all feel the urge, deep within, to escape?

Every day, in a bid to connect, I find myself reaching out to nature – whether that's tuning in to Planet Earth II, re-reading a Herman Melville epic or simply staring into an illustration of the natural world. It’s these tenuous links to nature I’m drawn ever closer to, driven by a need to explore.

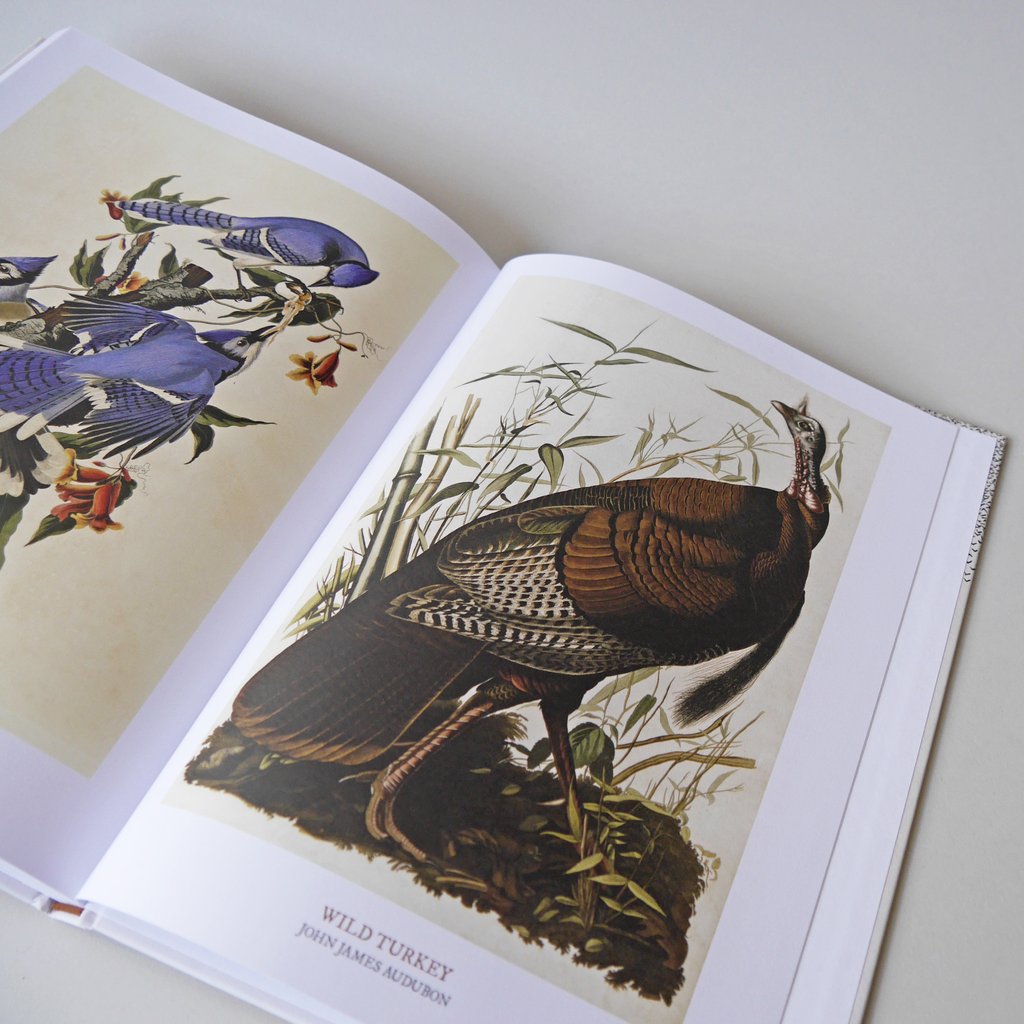

I’ve recently finished reading a graphic novel about the revolutionary 19th century French-American artist John James Audubon. In this epic story – On the Wings of the World – the painter’s life has been romanticised, with the spirit of the early American dream. I tend to develop small obsessions with explorers like Audubon, who forged a way in a new world – people conceding to the realisation that they need to be with nature.

On the Wings of the World, Fabien Grolleau & Jeremie Royer

It was these explorers who led the way in understanding the world they lived in. In Audubon’s case it was painting the wild birds of North America that took hold of his life. He dedicated himself to seeking out every type of bird, painting them in an ‘artful’ manner, depicting the natural world and its rich diversity in ways that were unorthodox to scientists at the time. They thought he took too much theatrical licence. Illustrating was also vital to Charles Darwin. Without any camera equipment on-board The Beagle, he constantly sketched and scribbled, which shed light on how new species looked to those back home. In later years, he theorised from his evidence how all of life is beautifully connected.

In a city where being able to see the Milky Way at night is a rarity, little acts of defiance spring – rooftop allotments, urban beekeeping and a cosmopolitan infatuation with houseplants. Here, another bid to connect an urban audience with nature has surfaced: Wild Life Drawing. These are workshops with a key difference – real-life-moving animals are the ‘models’. The idea is the brainchild of visual artist, illustrator and natural history enthusiast, Jennie Webber. Her aim is to inspire an appreciation for the natural world and an understanding of animals, allowing us to harness our own creativity and a childlike curiosity akin to Audubon’s own.

For some reason I feel more inclined towards exotic species of animal, so I sign up for a workshop sketching large lizards. Jennie works with animal handlers, animal sanctuaries and charities that have earned an excellent reputation and for this class, she had carefully chosen Snake’s Alive.

I watch the handlers take out the first reptiles – a Savannah monitor lizard and a python. He places them on the long table. Mia, the python, slithers around, while Hugo sits there obediently, not moving. He immediately charms everyone, and it’s strange to see just how docile he is, surrounded by eager sketchers.

Pete from Snakes Alive introduces the family company, which is based in Essex. They have been operating since 1996, largely offering interactive educational events for children, as well as supplying reptiles for private events. They also act as a sanctuary. Pete goes on to explain that Hugo, and the vast majority of their animals, are in fact unwanted pets, which leaves me feeling slightly dejected but I’m rallied by how affectionate the handlers are with their lizards; the animals are fully acclimatised to being around humans. Hugo, in particular, has formed a bond with Pete, who continues to stroke him gently under his chin. On watching this, that child-like wonder is brought back to me in an instant.

Simply sitting and observing this curious Man-Reptile intimacy seems to be relieving my stress, but I remind myself that I need to start drawing. I’m naturally hesitant, being not particularly confident person with a paper and pencil. I don’t know exactly where to begin. On Jennie's advice, I start with the eye. It means noticing that Hugo is now staring at me suspiciously. Does he know what I’m thinking? That I haven’t drawn an animal since 2009? Stop staring at me Hugo.

It’s a shameful admission that I haven’t picked up a pencil for years, but Wild Life Drawing is open to all – beginner and fully fledged artists – the latter I’ve noticed have brought along slick fine liners, felt tip brush pens and even scissors and coloured paper to create whimsical abstract shapes.

Jennie is moving around between participants, giving tips and encouragement. With some further advice, I break my sketch of Hugo down into simple shapes – slowly drawing the outline, then deciding to fill in details at the end. Hugo is an ideal model as he seems to like sitting still for a long time.

We’re lucky with Hugo’s dormant pose but when I move onto Mia, I take a photo for reference. She is a lot sleeker, perhaps a bit enigmatic in personality too – or am I being too presumptuous? Anyway, I start with a slender curve and emphasise her shadows. I feel like she couldn’t care less about my secret drawing shame, so I am more confident. Curiously, I find the snake more difficult to draw, perhaps because of her vivid pattern. Focusing on this detail reminds me just how intricate the texture and pattern of a python can be. I channel what I consider is my inner-Audubon, trying to capture Mia in a dramatic or unusual pose, fangs out and hissing loudly, but my imagination doesn’t quite match up with my pencil, so I focus instead on what I’m actually seeing. By focusing on the proportions and articulation of the shapes, I’m actually getting more in touch with Audubon.

I begin to understand why Wild Life Drawing feels so compelling. I’m learning about the animals at the same time. Education is fundamental in these workshops. As well as the classes starting with an in-depth introduction, we also learn about their behavioural characteristics. Hugo, the savannah monitor, I learn, is not actually this chilled out in the wild. He’s fully domesticated and used to being spoiled. They have a varied diet consisting of grasshoppers, crickets and mice. I learn about the ethics of feeding live animals and, most importantly, about the animal’s long-term welfare and the global issues threatening species in the wild. A proportion of Wild Life Drawing’s ticket sales goes directly to the handlers and a share is also donated towards the conservation and protection of the animals.

As well as workshops held in London, Jennie also hosts events at more scenic venues such as Woodberry Wetlands, an urban nature reserve and reservoir in Stoke Newington that was recently opened by Sir David Attenborough. Interestingly, the area has been closed off to the public since 1833 and was considered wasteland. It has since been transformed into an urban oasis by enthusiastic volunteers, and now welcomes kingfishers, reed warblers and dragonflies. The project is a breath-taking achievement that has reversed the effects of development.

For city dwellers, encouraging with wild spaces can be unsettling but perhaps it's the key to improving our quality of life? The hidden psychological benefits are crucial to our emotional well-being. It feels sensible not just to introduce plants, trees and greenery into the city and into our homes, but also to seek engagement – where all the senses might reap the reward of what it means to live in the natural world.

Back at our drawing class, I haven’t quite been able to capture these animals in either a naturalistic, theatrical or scientific pose, like Audubon once did. But despite reassuring words from the others that my drawing skills aren’t that bad, I’m undoubtedly encouraged to attend more classes, both to improve my skills and also to learn more about other species of animal and their continued conservation. The class reminds me why I feel strangely drawn to the great 19th century naturalists. A link to nature permeated Audubon. His naturalist spirit can help us all and with many of us city dwellers having little to no contact with the natural world in our daily lives, Wild Life Drawing’s aim to reconnect us has never felt more important.

You can learn more about Wild Life Drawing and book classes here.

Alfred Addis is founder of Eastern Biological, London's first independent natural history and concept lifestyle shop. Take a longer look at some of their inspiring sale items in the online store.