We associate blueprints with architectural drawings but Los Angeles artist and astrophysics enthusiast Lia Halloran has used the cyanotype technique for her extraordinary series Your Body Is A Space That Sees. Her prints pay long overdue homage to female astronomers – depicting craters, comets, galaxies and constellations. Rosie Gailor talks to Lia Halloran about her stellar work.

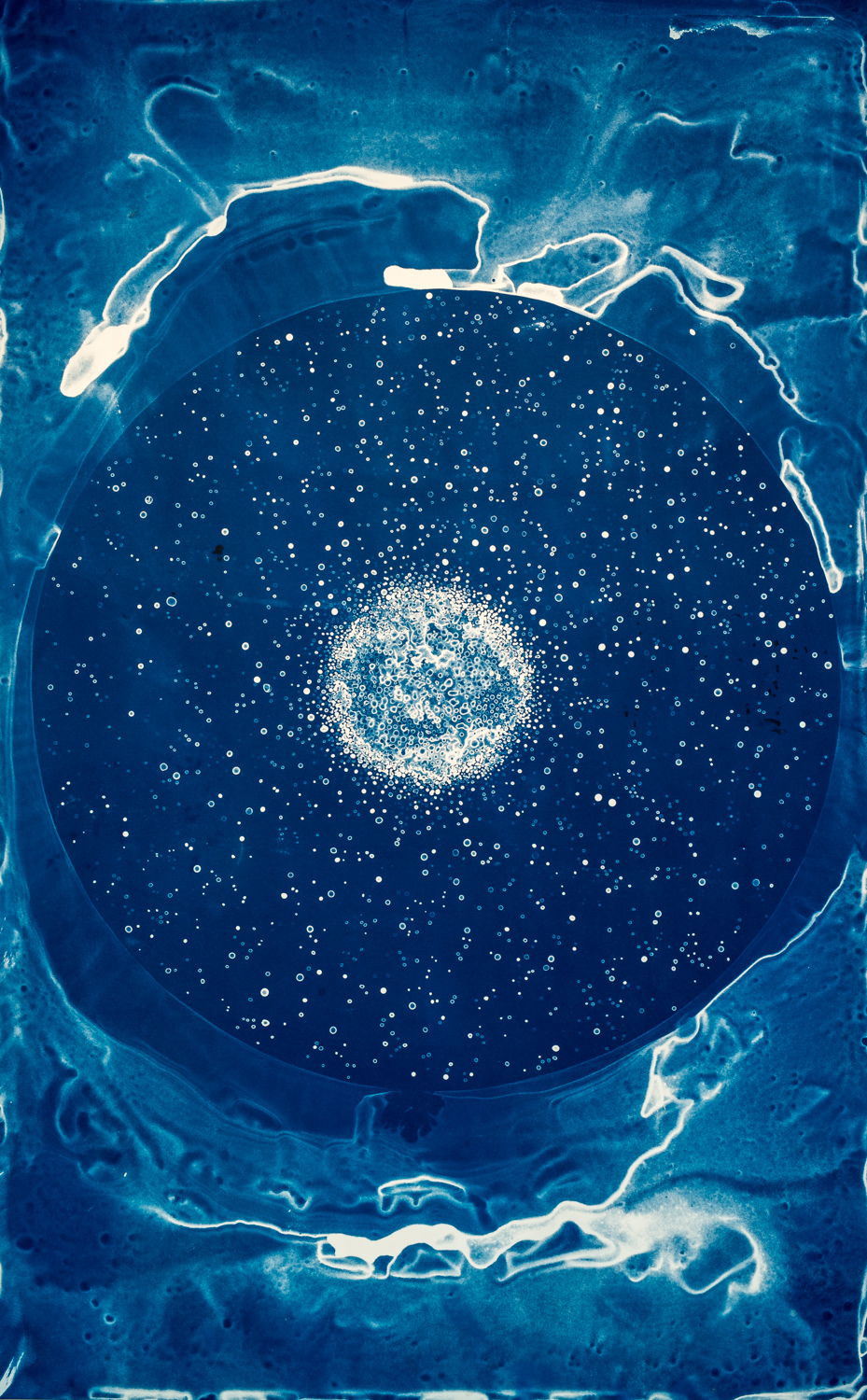

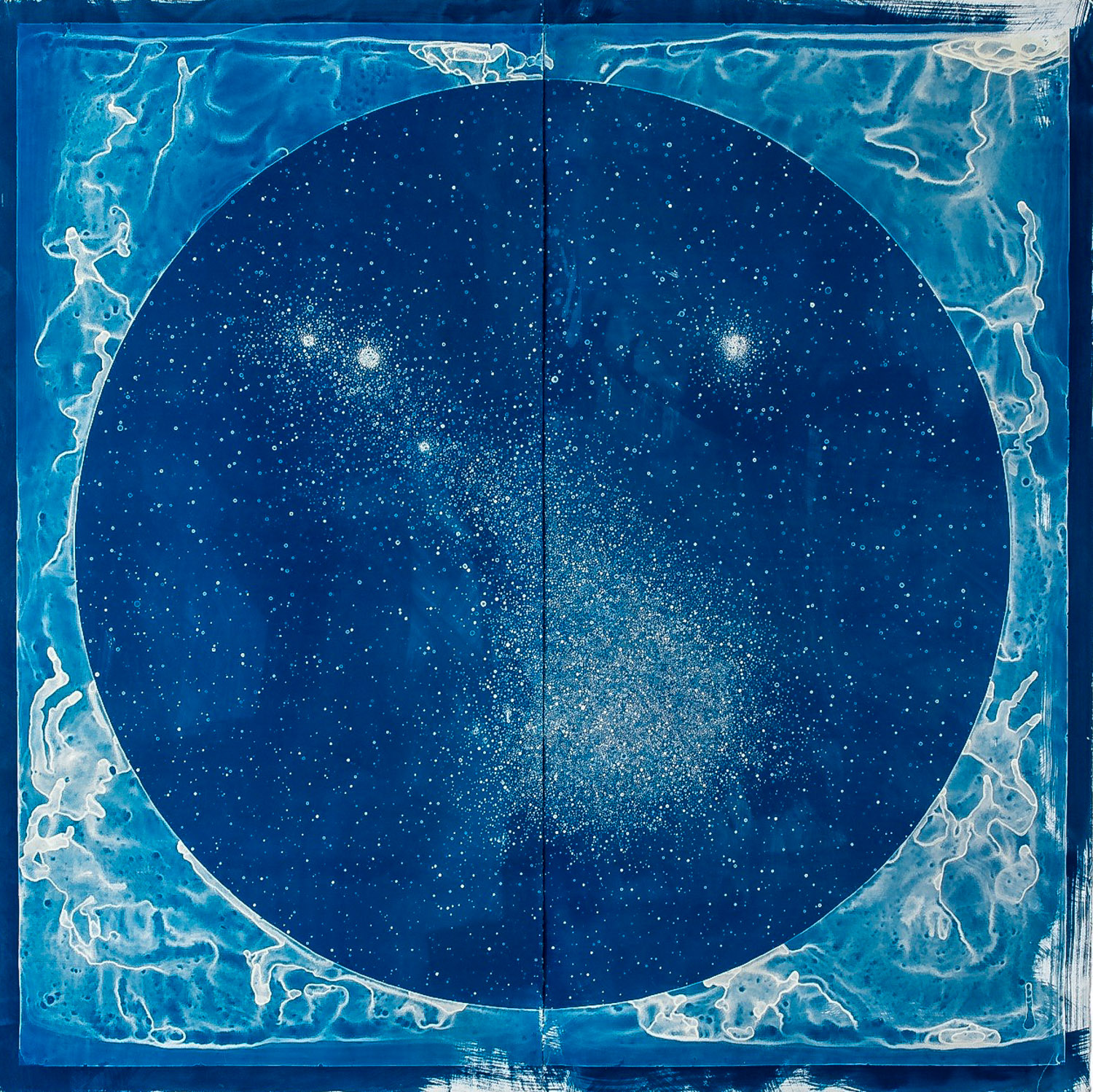

Lia Halloran: Globular Cluster, 2015, cyanotype, painted negative

Cyanotype is a photographic process using iron compounds instead of silver (used in traditional black and white photography) to create the photo-sensitive emulsion. This produces a cyan-blue tint.

Lia prints her huge cyanotypes from ‘cliché-verre’ negatives, which literally means ‘glass picture’. Nineteenth-century painters used this method by etching, painting or drawing onto a transparent surface, such as glass, to create a negative. This was one of the earliest forms of producing images before the advent of the camera.

Where did the idea for this project originate?

I was interested in the scientific taxonomies that gave rise to the lineage of science as we know it. I first made a series using the periodic table of elements as a jumping point, another series about cabinets of curiosities and the science museum in Florence, Italy La Specola, then I turned my focus to create 110 paintings based on Charles Messier’s astronomical catalog of deep sky objects. He was a French astronomer in the 1700s who was looking for comets and accidentally found a blurry object he named M1 (now known as the Crab Nebula). He was frustrated to find this unknown object instead of a comet and started a catalog of 'things to be avoided when out looking for comets'. These irritating objects he was accidentally discovering turned out to be nebulae and galaxies.

How amazing! So on your site it says you’ve always loved creating a crossover between art and science. When did you first discover your personal link to this theme?

The first time I used science as a bounding point in my work was when I was in graduate school at Yale as a painting student, and I read Kip S. Thorne’s book, Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy. I loved the way he described the experience of the stranger parts of the universe; it allowed me to approach the subject and make it personal.

You’re a college professor who teaches not only art, but courses exploring the overlap between artwork and science. Have you found that your research into the history of female astronomers has given you a greater insight into this overlap?

I feel lucky to be able to design courses that are interdisciplinary. Where I teach, Chapman University in Southern California, is extremely supportive in championing unique coursework. I like to think of the classes I develop and teach by asking myself: 'if I was 18 and took a class that would have changed the way I think about art while supporting my curious nature, what would it have been?'

In ‘The Intersection of Art and Science’ my students go to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and learn about current missions, and we do a night of observing on the famous 60-inch telescope up at Mt. Wilson Observatory. Last year we even did a sound bath out at the Integratron in Joshua Tree. All of these unique experiences (I hope!) make my students more inquisitive and invested in their own work. The first time I taught this class we were at Mt. Wilson and I had just looked through the telescope and viewed Saturn and it’s just so breathtaking. No matter how many times you’ve seen Saturn in pictures, it becomes all yours in the view finder. A private reminder that there are these giant spherical objects out there, going around the sun just like us. I turned to one of my students without thinking and exclaimed: 'I’m just so happy I’m in this class!' to which she replied: 'Lia… you’re teaching this class!'

Anytime I’m excited about a subject I’m researching, I try to bring that enthusiasm and information into my classes - and that includes my research on the history of female astronomers. I love sharing this history and hidden lineage, and hopefully it will challenge preconceived notions about the course of history and these important figures that we have left out.

I’m thinking of the astrologist Vera Rubin’s struggle to gain respect in her quest of astrological science, mirrored in her own daughter’s experience. Was there a feeling of honouring the powerful women who made the discoveries you’re re-envisaging in this series?

Absolutely. Your Body is a Space That Sees is a re-investigation of the lineage of astronomy, using discovery as a timeline. The project is all about honouring, celebrating and illuminating the rich and important work these astronomers did. When doing the research I focused on the group of Harvard Women in the late 1800’s, known at the 'Harvard Computers' or 'Pickering's Harem’ and I couldn’t help but think, sadly, that was a very different time. It’s upsetting that they were paid less than half the wages of men but it was, after all, the 1800s and this was 40 years before they got the right to vote. Then you look at the incredible work of Vera Rubin and Jocelyn Bell Burnell - who are making major breakthroughs NOW in the past couple of decades. Where is the Nobel Prize committee?

On your website your other artwork is featured beautifully, and you have a clear voice that shines through each one of your collections. How did you decide on using the Cyanotype technique?

There’s something about that blue that I find simultaneously represents both the darkness of the sky, and the vastness. Also for me, that colour is emotional and efficiently nostalgic. I’m hoping it will evoke a sense of blueprint in the viewer (although maybe young viewers don’t have the same relationship to printing). The process itself of making and painting to then use as a negative in the process was a specific decision to give a nod to the history of photographing the night sky using glass plates. My paintings are in essence, giant (painted) glass plates. But, in my case, it’s a painting used to make a print of images of stars by using our own star (the sun).

There’s a powerful book, written by Lauren Redniss, that tells Marie Curie’s life story through a mix of Cyanotype-printed artwork and typography. Do you think the use of this technique empowers the story of these women and their discoveries? How different would Your Body is a Space That Sees be if done in a different technique?

Thanks for the recommendation – I look forward to seeing that book! For my work, what I’d hope for is for the viewer to be drawn to the work and imagery of the cyanotype on its own. Regardless of what is known about the subject matter, the hope is that the scale and the imagery will compel the viewers to learn more, and share my fascination in the history and story of this group of women. History can tell the specific story but I’m interested in presenting the experience of that story. I’m thrilled that Dava Sobel has written the history of this group of women in an incredible book titled The Glass Universe, which comes out December 6th... go buy it!

Tell us – do you have a favourite piece?

‘The Magellanic Cloud’. This one was the first large work that was made (a bit over 6x6 ft) and when it went up on the wall, I felt like I was on a spaceship looking out a portal to this galaxy of stars. The Small and Large Magellanic clouds are nearby galaxies that can be seen from the Southern Hemisphere with the naked eye. When I was in graduate school and visited the major observatories on a grant, between my 1st and 2nd year of school in Chile, I just could not believe there were nearby galaxies right there. Why wasn’t everyone talking about this all the time? Seeing them for the first time parallels the spirit of the whole project: the experience of discovery. The glass plate I used as a reference is also one of the most spectacular examples in the collection at Harvard, with the initials ‘A.J.C.’ (for Annie Jump Cannon) on the sleeve.

I also loved reading about the process on your blog. I fell a little bit in love with Henrietta, your original printing machine.

Henrietta! My studio assistants and I spent a lot of time making this giant contraption, which we loving named Henrietta, to try to reproduce printing in the sun. Alas, her output light wasn’t as powerful as we needed and we had to take her apart. That sounds a bit macabre but we name everything in the studio after female astronomers. Saying, 'Grab Hypatia and Annie Jump Cannon and I’ll meet you with Herschel' actually translates as 'Grab the GoPro and external drive and I’ll see you in the car!'.

It is, of course, beautifully poetic that the sun gave the prints the ultraviolet light necessary for the final step of the process. Do you think there’s an equally unexplored crossover between other art forms – i.e. literature, film, music – and science?

Absolutely. I’m thrilled that the art science connection is being highlighted and celebrated and I look forward to seeing projects that straddle the boundary between disciplines.

Also, congratulations on the book you’re creating with Kip S. Thorne. This is a book that combines your scientifically-inspired artwork with his scientifically-inspired poetry; what do you hope to explore in this book? Have you already started to find prominent themes popping up?

The book is now quite far along - I’ve made over a hundred small paintings, about 70 percent of which will probably be cut out. It’s a different kind of science book featuring Kip’s poetry and my paintings, describing black holes, time travel, and wormholes. The space traveller I’ve painted is actually my wife Felicia, so it’s also a very intimate book.

Just before I go – wanted to say how much I loved looking at your ‘Elements’ collection, which is your reinterpretation of the periodic table. It is beautiful, as is all of your work. Have you any idea which fabulous bit of the scientific world you’re going to engage with next?

Last year I started something I’ve wanted to do since I was a kid – flying. I am member of the JPL/Caltech Flight Club and have been taking lessons once or twice a week for the past year. It’s been one of the best things I’ve ever done. Being alone in a plane is like looking through the telescope at Saturn: unbelievable. It’s made me think about drawing and trajectories differently. I’m not sure what is there as a body of artwork, but I’ve started filming my flights hoping to make something with them someday.