Writer, historian and self-confessed dystopian fiction enthusiast, Lela Tredwell explores her grief for the fallen on Remembrance Day for Lost Species

2016 was the year of the Bramble Cay melomys – a small rat-like creature that once lived on a low-lying coral cay on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Officially extinct as of May 2016, it is the first recorded mammal to have been wiped out by the effects of anthropogenic climate change (caused by humans).

The idea of humans outranking other creatures is not a new one. It pre-dates the Chain of Being of the Middle Ages (a visual metaphor for a divinely-inspired hierarchy of all forms of higher and lower life), and can be tracked back to ancient civilisations, including the Greeks. By the 21st Century, however, we seem to have well and truly asserted ourselves as the super-police of the natural world.

Are we competing with the earthworm, wanting to get top spot for the species impacting most on the world? If so, we’re still way off worm status. The Chain of Being put earthworms at the very bottom of the pyramid, ironic then that the humble creatures should have such an essential role to play on earth. Much more so, it now turns out, than humans.

As vultures decline in India, in part due to a man-made drug, carcasses litter the land and stray dogs move in; cases of rabies have spiked. In upsetting the balance of nature we will only come to hurt ourselves. David Attenborough famously said that if we don’t do something about our population growth, nature will. It calls to mind the plight of the bumble and the honey bee, which tirelessly pollinate over a third of our own food source yet we allow them to be poisoned by agricultural chemicals. My grandfather was a beekeeper; it breaks my heart.

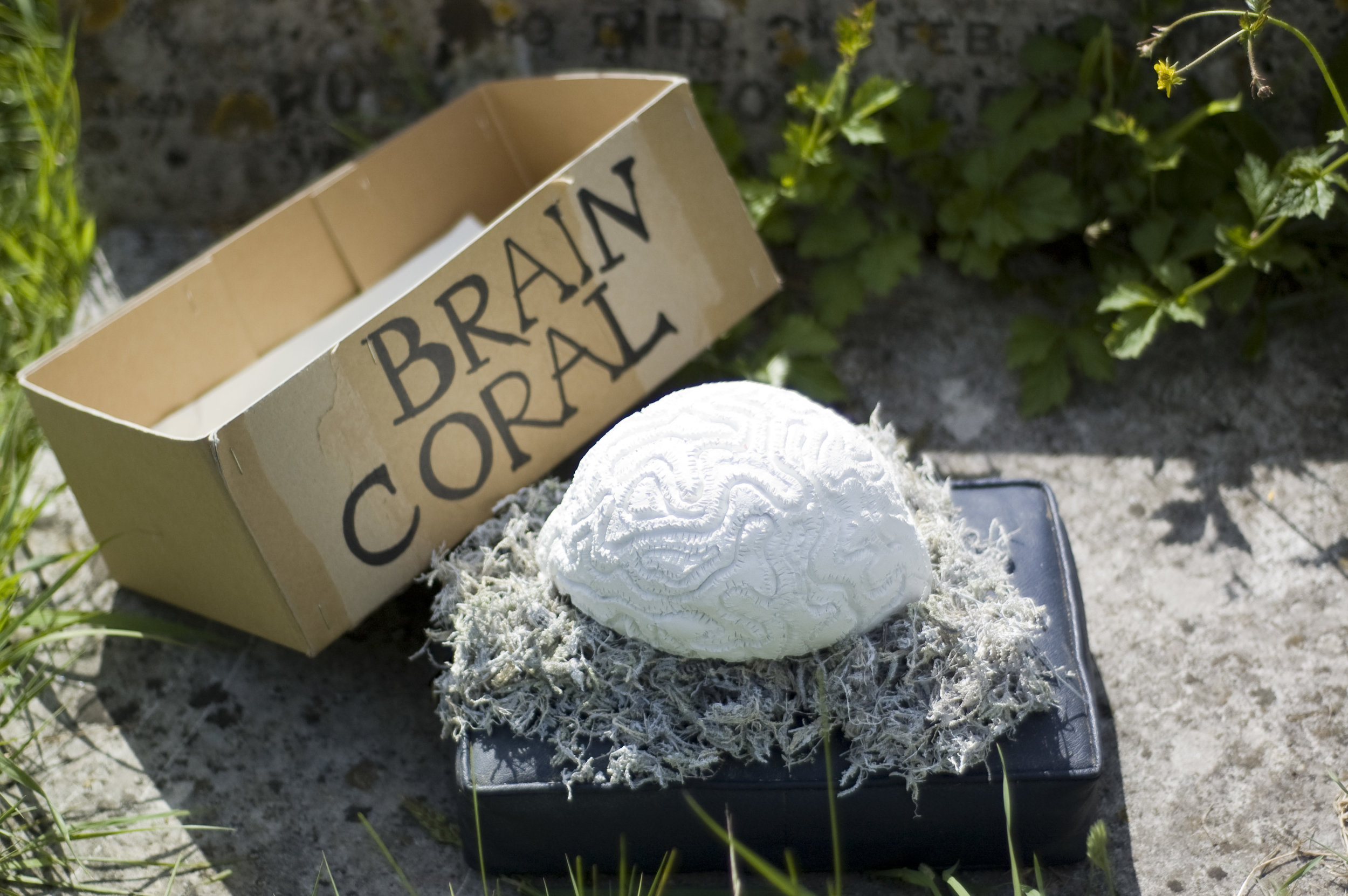

A memorial made by Eri Meacock

My own grieving for extinct species started at a young age, when I discovered the oozlum bird was really dead for good, if it ever even existed, from a Carry On film. Up the Jungle suggests the oozlum bird might have got away but a shaking of the head from my mum confirmed the worst. So I’ve been carrying that weight of guilt and disappointment – along with the other disturbing elements of early exposure to Carry On films – around with me for a long time. At primary school I sponsored animals, supported Greenpeace and wrote letters to newspapers, which I would sometimes send but often stick them proudly in my project book. I used to fantasise about standing aboard Greenpeace's Rainbow Warrior ship screaming sense through a megaphone.

But despite valiant efforts, in the last 40 years our planet has lost half its wildlife (WWF). Three species become extinct every hour and many more stalk the endangered list.

Perhaps grieving the loss of fellow species is a strange concept. But why not when everything is connected? Species extinctions are invariably linked to the loss of cultures and places, and we haven’t had the rituals to adequately grieve – until now.

Remembrance Day for Lost Species has been held in Brighton on 30 November for the past six years and its impact is spreading. Previous events saw a Viking burial at sea for the Great Auk, 'flying' the last passenger pigeon to the Life Cairn on Mount Caburn and the Thylacine Tribute Cabaret – a theatrical homage to the Tasmanian tiger. It is a chance to share the stories of those lost in the sixth mass extinction, and to renew commitments to those remaining.

The impetus for the event started when Persephone Pearl came ‘face-to-face’ with a taxidermy thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) in Bristol Museum. She felt a deep sense of grief for the marsupial carnivore, which was shot to extinction in 1936 by European settlers. She wanted to break it out from its glass case and give it a proper burial.

Caspian Tiger Shrine, September 2013

In Margaret Atwood’s dystopian masterpiece Oryx and Crake, characters adopt the code names of extinct species. Which would you choose? The West African black rhinoceros, the quagga, the Caribbean monk seal? For me it's Steller's sea cow.

Discovered in 1741 by Arctic explorers, who estimated its population to be 2,000, these sirenians were wiped out only 30 years after meeting humanity – killed to provide seal hunters with meat on long journeys. No specimens remain today but we know they measured over 30 ft and weighed 22,000 lbs, much larger than the surviving manatee and dugong. They had small heads, broadly forking tails and no teeth. They used stumpy flippers near the front of their bodies to move themselves over rocks and hold fast to them in rough seas. They had little ability to submerge and so they floated on the surface, eating kelp and seaweed – an easy target for harpooning. So today, on Remembrance Day for Lost Species, I will light a candle for the fallen Steller’s Sea Cow. How long will it be before we are lighting flames for the extinct snow leopard, orangutan and polar bear?

A child visits the ‘grave’ of Bombus Franklini during the Funeral for Lost Species.

One Native American saying teaches that we are merely borrowing the earth from our children. What then will future generations think when they discover that we have wiped out part of their future world, and they must live on a planet without the biodiversity that kept balance?

In a recent Channel 4 documentary, China: Between Clouds and Dreams, school children have been investigating the decline of the spoon-billed sandpiper, which is on the brink of extinction but has been given a recent reprieve by a breeding program in Russia. The children are asked to keep 'spoonie' safe during its migration to the warmer climate. The children found that chemical factories in their area are having a detrimental effect on both the wildlife and human population. The vast mudflats south of Yangkou on the Jiangsu coast where their beloved ‘spoonie’ birds feed are being contaminated.

On 30 November 2015, Remembrance Day for Lost Species cast a bronze bell which was tolled 108 times to mark the passing of extinct species. This year, they are encouraging people to make their own tributes to lost creatures – whether that be by lighting a candle, hosting an event or simply sharing their thoughts on Twitter. Lest we forget, we are all in this together.

Feral Theatre’s Thylacine Tribute Cabaret, September 2016.

Read more about Remembrance Day for Lost Species at onca.org.uk/ongoingprojects, join in with an event on their Facebook page and share your extinction tributes on Twitter.